The chickadees have been singing again and it’s time to order seed potatoes and onion starts. The year has barely had time to rub sleep from her eyes, and the frozen peaches are not even dented by my hunger for their winter warmth, and I feel like I just got the potatoes stored away in the paper bags and moderate temperature that seems to have—mostly—succeeded in keeping them edible through the winter.

How can it already be time to think of choosing carrot and lettuce seeds, of where to plant beets and how to make more room for green beans, of the soil’s stirrings and the young yawns of growing things in my garden? It might be months, still, before I can visit the sweetgrass and turn the soil, but it is time, already, in the midst of this winter, to be planning for the next.

I was away most of last week committed to what I’lll broadly call parental duties, long hours of chaperoning, most of which took place in the confines of a hotel my kid and I rarely left. By the time the commitment was done, my body felt stunned from lack of movement. I spent two hours on Monday walking through town and along the river trails, relieved at the sight of water, the freedom to wander, the flurry of chickadee-company, and the surprise of what might be a new construction along the riverbank.

The drive home had been painstakingly slow, through hours of fog that seems to mark most of this winter’s personality. I hadn’t seen Moon at all for what feels like weeks until three nights ago, moonglow through the fog, Her bright self mostly hidden from the skies I live under until the dark, dreamy hours of this morning.

I watched Her there for an hour, remembering what moonfall feels like and ignoring my usual routines. A few hours later, on our way to school, She was cast slight pink in the pre-dawn sunlight that crept out from behind the mountains.

Who else, I wondered, might be watching that alpenglow wrap itself around Moon?

Why put all those words and observations on a page, why share them with you? What is this human urge to story? To shape the narratives we see around us, to call attention to beauty and comprehend grief? Why write?

I’ve seen this question lobbed about since I was old enough to understand the concept of philosophy, if not philosophy itself. What is the compulsion to create? Why do we care so much?

I don’t have any better answers than anyone else. All I know is that I become a grumpy, unpleasant person when I don’t write. It’s a compulsion. It’s joyous and beautiful, to be lost in a narrative, but it’s also demanding and ruthless. Writing left me once for a few months, just flat walked out the door. I had thought that if that ever happened, if I couldn’t create, I would feel bereft. I thought I wouldn’t know myself. But what I felt was free. I kept thinking of all the things I could do with my life now that I weren’t driven to shape them into narrative of some kind.

Writing came back after about three months of that release, as if wandering through the door after an argument: “I just went for a walk. Needed some air.” And there we were again, back in a lifelong need to story, to do whatever it is that happens between my interaction with the world I exist in and the way my mind—or whatever it is—decides those experiences and thoughts should sound, feel, taste.

Writing is very, very weird.

The novelist Elif Shafak wrote recently of a 16-year-old girl in Afghanistan who loved to read, who dreamed of libraries and pizza and of meeting Shafak herself after reading one of her novels, and who was killed by a suicide bomber.

“I am tired of being attacked and stigmatised and labelled by fanatics and zealots and ultranationalists only because I am a writer,” wrote Shafak.

“But when I feel so down and despondent, I think of Marzia and I think of every other aspiring novelist and aspiring poet in the world who were never given even half the chances that were provided to me throughout my life: books, bicycle, pizza, electricity . . . I will never belittle any of these.

I have no doubt that Marzia would have become an amazing storyteller if only she had been encouraged and if only her life had not been brutally taken away from her. I feel like all of us in the writing community owe something deep and precious to all the Marzias on this planet. We owe them a sincere commitment to literature.”

Writing is weird but it’s also necessary and it exists far beyond any arbitrary measures of success and failure. I’ve written before of my stepmother’s great-aunt, the Russian poet Marina Tsvetaeva, and her life that knew little but hardship and brutal loss, and how throughout it she wrote poetry so meaningful and beloved that to this day there are museums dedicated to her all across the country.

At the end of my life, all I can ask for is that I’ve done the best work possible and used whatever skills and talents I’m fortunate enough to have to create something of beauty and meaning. Maybe one book, one essay, one single line, might reach the one person who really needs it.

“It is as simple and as powerful as that,” wrote Shafak.

“The love of books and libraries and the joy of reading. This is all we need. This is why we keep on writing.”

There’s something more, too: that delight and spark that Marzia knew reading and writing held for her, the world-opening potential of stories that I remember feeling at her age.

I think many of us write because we can’t help it, because it’s a jealous lover or a hunger that can’t be sated or whatever metaphor works for you. When that leaves us, even if it’s only for a while, we still have what’s left: we write for one another. And what a gift that is. Stories can break empires; they can tell our hearts we’re not alone. They make us laugh. They make us grateful to be alive.

It’s been foggy and somewhat rainy for days and days, but today the cold was biting again. I didn’t dress warmly enough and my fingers were numb by the time I dropped off my kid at school.

As I was turning away from the building, blowing on my hands, I saw a cluster of ten-year-olds, their pom-pom hats wobbling as they turned, ignoring the school bell to send frosty breath up toward a bald eagle soaring low overhead.

The crossing guard watched, and me, too, and we smiled at each other, and I held close the gratitude I always feel at the sight, at watching children hold their breath because they see a bald eagle and they know. You pause for such birds. The soul bows. And I hold the knowledge I wish these kids never to have, that my gratitude is weighted with the knowledge that bald eagles were almost extinct when I was growing up.

High on the mountainsides just outside of town, the first light of dawn brushed the snow, the same light that was coaxing alpenglow from Moon. A flurry of snow rose in the light, over three thousand feet above me, and I wondered which of those sunshot flakes will be the first to meet spring’s young strawberries.

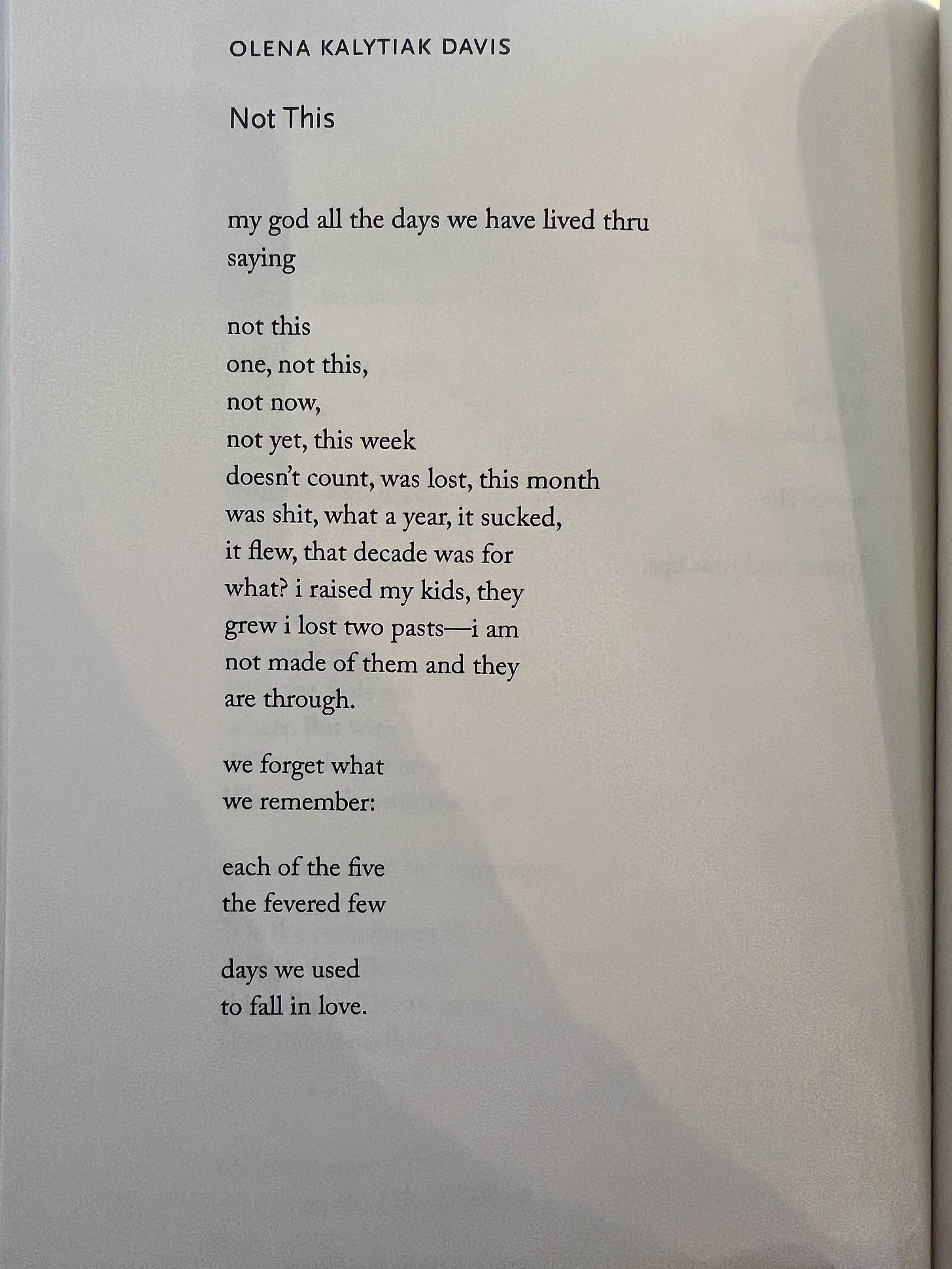

I received a surprise care package this week from a friend who knew I’d been going through some difficult personal things recently. Among tea and a kind note were two books of poetry. This poem, titled “Not This,” by Olena Kalytiak Davis, appears in one of them, The World Has Need of You: Poems for Connection, and I keep rereading it, finding something new to catch my thoughts each time.