Welcome back to On the Commons! For those of you who are new here, On the Commons is a newsletter exploring ownership and its inevitable injustices, investigating centuries of philosophical and legal arguments made in defense of private property for a much simpler explanation: theft. Or in other words, “I took it; now it’s mine,” and the consequences both large and small for our shared world.

This is an updated, slightly revised version of a post first published on 31 December 2021. This is the third in a series of essays republished from earlier years. The previous one was on the Doctrine of Discovery.

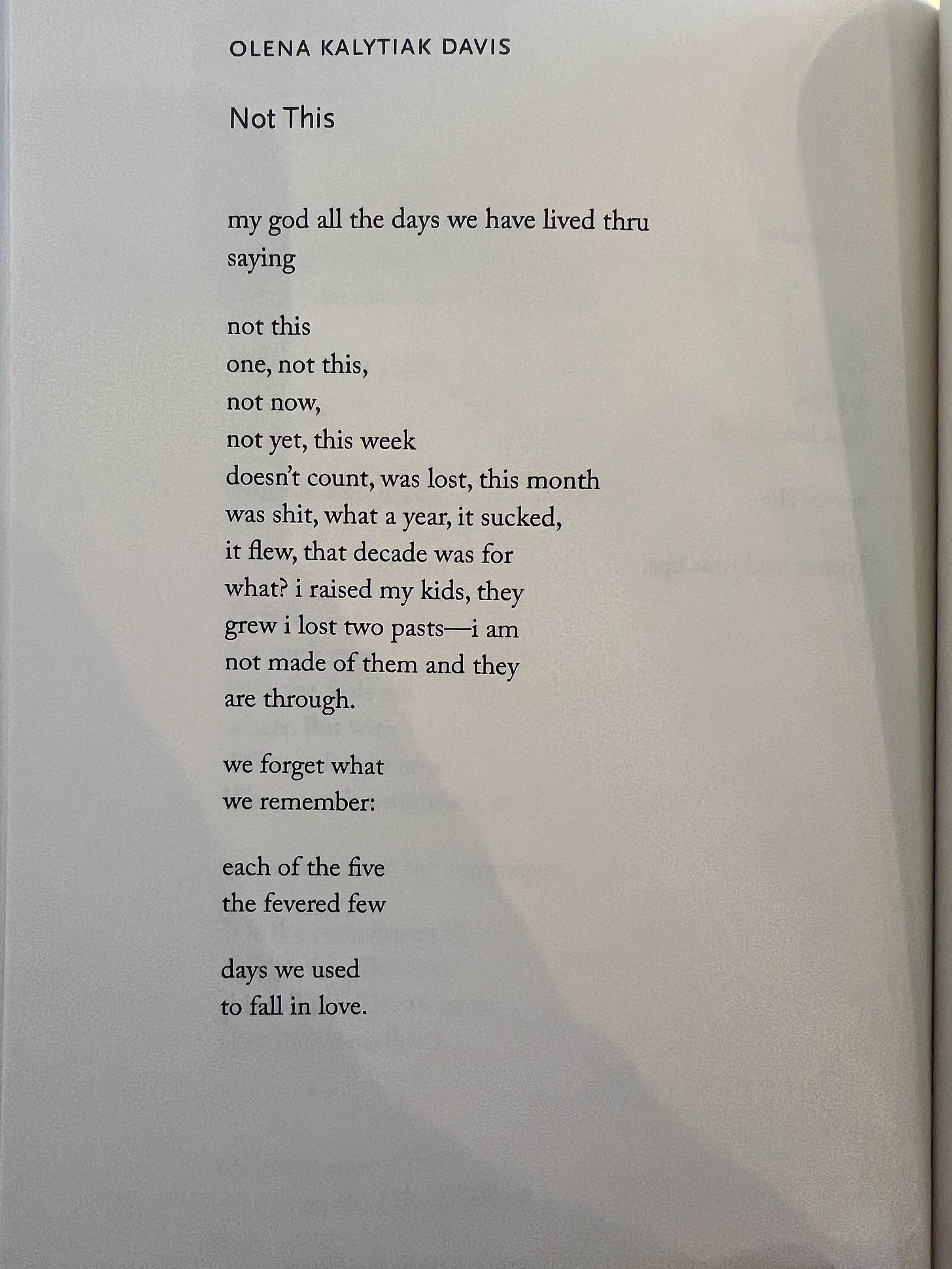

Both top and bottom photos are of No Trespassing signs on the fence of land owned in my town by the Burlington Northern-Santa Fe railway company.

The Boston Tea Party is one of the defining stories of America’s founding as a nation. I remember learning about it year after year in school in the 1980s. Probably every American kid does. What was never said in those scrappy little classrooms across Montana is that the story of the Boston Tea Party is also one of the sharpest tools wielded in defense of the mythologies that make up the American ideal. The fact that it was an illegal riot that destroyed private property doesn’t just get glossed over; it’s never presented that way, not in the U.S. anyway. To present it that way would fly in the face of the American ideology that private property is bedrock. Instead, the story is presented as noble: the little nation that could refusing injustice imposed by a far-off monarchy.

What also gets glossed over is that the impetus for the riot wasn’t simply taxes; it was taxes imposed by government in order to benefit a private corporation.

The struggle over taxes in the British colonies of North America had been ongoing for years. The tax on tea, however, had a second purpose besides enriching King George III: the British Parliament wanted to keep the tea tax as a symbolic acknowledgment that the government maintained its right to tax the colonies, but they also wanted to help the East India Company claw its way out of debt. The story of the Boston Tea Party, the real one, points to the longer history of government enabling corporate power and profit until it essentially becomes an arm of the corporation itself.

The East India Company had its own private army. It in effect controlled all of India at one point, nominally representing Britain’s interests but serving its own.

Swarnali Mukherjee has written extensively in Berkana about what the British Crown and the East India Company’s actions meant for the economy of India. I encourage you to read the entirety of her essay on this subject, to understand the importance of the point she makes:

“The construction of railways was funded by Indian taxpayers, and the economic benefits often flowed back to Britain in the form of profits pocketed by British shareholders. The total wealth drain of India under British rule, in today’s value is an estimated $45 trillion.”

As with many of our modern corporate-government revolving doors and mutual back-scratching habits, the interests of the corporation often enveloped, or became, those of the state, as noted in this Financial Times article on the East India Company and its implications for modern capitalism:

“The EIC remains history’s most ominous warning about the potential for the abuse of corporate power — and the insidious means by which the interests of shareholders can seemingly become those of the state. . . .

For just as the lobbying of the Anglo-Persian Oil Company was able to bring down the government in Iran and United Fruit that of Guatemala in the 1950s; just as ITT lobbied to bring down Salvador Allende’s Chile in the 1970s and just as ExxonMobil has lobbied the US more recently to protect its interests in Indonesia, Iraq and Afghanistan, so the EIC was able to call in the British navy to enhance its power in India in the 18th century. And just as Facebook today can employ Nick Clegg, the former UK deputy prime minister, so the EIC was able to buy the services of Lord Cornwallis, who surrendered Yorktown to Washington.”

It’s a long but excellent article (and unfortunately I think now paywalled), detailing the Company’s permission to wage war, and instances of forced privatization across the world at the Company’s behest. It also points to England having isolated itself from the rest of Europe due to wars over religion (I assume the author was referring to the abandonment of Catholicism and establishment of the Church of England) as a factor prompting the country to look for markets outside of Europe, a vital ingredient for colonialism:

“The English were forced to scour the globe for new markets and commercial openings further afield, and to do so they had no compunction but to use, for the first time in history, unbridled corporate violence.”

One of the questions I keep asking myself is if government, of almost any form but particularly of the nation-state, has always existed to serve private interests. Its main claim to enforcement of law is a monopoly on state violence, most often employed in the name of protecting private property, rather than protecting citizens from harm.

This is obvious when you look at laws and police actions against something like constructing an oil pipeline. The pipeline is private property built in pursuit of profit; therefore, it qualifies for legal protection from the state even though it threatens clean air, water, and soil—even if it takes others’ private property in turn. The U.S. government’s power of eminent domain, after all, was first used for private gain when railroads were being built across the continent, and has continued to be wielded in the name of private profit ever since—the Supreme Court decision in Kelo v. City of New London (2005) and the Pennsylvania District Court case granting eminent domain to a pipeline builder over the objections of a family of maple tree farmers in 2016 are only very recent examples of a longstanding pattern.

What to do about it is another question. Even democratically elected representatives are eager, as we see all too clearly every day, to promote corporate interests over that of their constituents if it assures them a safer and longer place in a seat of power. We need democracy and the right to vote, but those tools aren’t enough to assure a livable planet and lives of dignity. They are necessary conditions, but not sufficient.

There’s a tendency to just say, f— it, burn it all down and start over. But that’s been done more than once throughout history, in several places within living memory, and all it results in is a lot of suffering and the same cycles starting over again. It’s as if there’s something broken at the center of humanity, or at least a sizable portion of humanity, and we’re never going to find a better way to live together until we clearly define the shape and scope of that brokenness. As long as we* accept structures that prioritize private profits over life and health, pollution and structural injustice is all we’ll get.

If I believed in the devil, it would be someone in a sharp suit promising me two or three generations of decent jobs in exchange for the water, soil, and air I depend on, with the added bonus of sacrificing my kids’ health and senses of themselves as free human beings. It is the purest kind of evil to smile and hand out some cash while snipping the threads that link us to life.

The stories we tell and accept about ourselves and others have tremendous power. If we can change the stories, maybe we can begin to change something about our lives.

Instead of trying to burn it all down, plenty of people focus on building from the ground up—better systems, better ways of doing and being and living: this profile of a local food and farm co-op in Washington is a reminder that even when things feel like they’re falling apart, there are people and networks all over the world trying to piece them back together. Montana’s Alternative Energy Resource Organization (AERO) has been working against corporate agriculture for decades, from lobbying for a different kind of Farm Bill that works for people and food rather than commodities, to producing the bulk of the country’s organic lentils and heirloom grains like kamut. Oakland’s Unity Council has also been working for decades on affordable housing, higher-quality food access, and integrated public transportation in Fruitvale, one of the city’s poorest areas.

There are plenty more. I’m reminded of these organizations and people every time I work on a story about urban planning, affordable housing, or pedestrian advocacy. They are everywhere. They just never get featured on cable news or the podcasts of so-called “thought leaders.”

Changing our systems to serve people involves all of these efforts. And they don’t have to be scaled up—they have most power and efficacy when they stay connected to a particular place and community. Instead of scaling up small, workable, place-based systems, we need to take out the support systems that keep oppressive conglomerations afloat, from tax subsidies to weak interpretation of anti-monopoly laws (which should always include what monopolies truly cost life). And of course to change the way a large percentage of human beings see themselves as co-existing with the rest of life, which is no small task after millennia of negating and oppressing this reality.

During a recent U.S. election cycle, my state elected a governor who ran on the tired trope of lowering taxes, “creating jobs,” and being a successful businessman. People in my state are actually very good at “creating jobs.” Small business owners sometimes feel as common as pine trees. Many of those jobs—upwards of 70,000—are dependent on a healthy commons in the form of clean rivers full of fish and public lands that provide the kind of solace and clean air that no job could touch.

It’s often hard to get people to acknowledge the existence of these jobs and the kind of healthy shared commons that make them possible because our idea of a “job” is so starved of meaning and hamstrung by identity and self-perception. (Journalism jobs have fallen by 65% in the last 20 years, for example, while coal jobs have fallen by 61%, but we don’t hear much about the former.) Working in a lumber mill is a job; working as a fishing guide is, too, but also somehow isn’t the kind of job you’re talking about when you’re voting for “job creators.” Real jobs means lumber mills, slaughterhouses, car factories, oil pipelines, tech engineers. It means hundreds of people, massive profits for the bosses, and a no-holds-barred attitude when it comes to environmental destruction. Maybe it’s the type of job or maybe it’s the number of people employed at each operation, but there are plenty of small businesses that somehow don’t count when it comes to political rhetoric.

This is just a story we’ve been told, one that people then tell one another. But we are capable of telling different stories. We just need more people doing so, and then acting on them.

The East India Company and various colonial governments were very effective at telling stories. They’ve left legacies of imperial pride that still resonate and warp people’s thinking today, and blind us to the dangers of corporate power. As that Financial Times article pointed out:

“We still talk about the British conquering India, but that phrase disguises a more sinister reality. For it was not the British government that began seizing chunks of India in the mid-18th century, but a dangerously unregulated private company headquartered in one small office, five windows wide, in London.”

The company did so with the support of the British Crown, and when the EIC was facing further debts from their activities and obligations worldwide, the Crown stepped in once again to help them recoup losses through a monopoly and tax on tea in what they saw as their “possessions” in America. To quote from the Boston Tea Party’s own museum:

“The British East India Company was suffering from massive amounts of debts incurred primarily from annual contractual payments due to the British government totaling £400,000 per year. Additionally, the British East India Company was suffering financially as a result of unstable political and economic issues in India, and European markets were weak due to debts from the French and Indian War among other things. Besides the tax on tea which had been in place since 1767, what fundamentally angered the American colonists about the Tea Act was the British East India Company’s government sanctioned monopoly on tea.”

The East India Company is one of many lessons throughout history of the dangers inherent in encouraging the mutual support of corporate and state power. There are countless examples to explore, like the land stolen throughout North America and given by the U.S. government to railway companies, with profits for the railway and timber industries continuing even to the present day. The timber company Weyerhaeuser, for example, first bought 900,000 acres from the Northern Pacific Railway in 1900, and now profits off of not just the trees grown on land they own, but on the land itself, which the combination of state and corporate power has turned into “real estate.”

Phrases like that—“real estate”—carry their own stories, their own burials of what land has been, could be, and is.

We can change what we believe, starting with what we think we know about history and the real, live world around us. We can tell better stories about what is possible and what we’re capable of. We need to, because corporate growth and greed will not stop taking and commodifying and destroying all that makes life worthwhile, nor will it stop fabricating stories that make vast numbers of people believe it’s inevitable, unstoppable, and probably for the best. We need more stories, better stories, and we need them everywhere in hopes that those stories can, over time, change what is.

Change takes a lot of time and a lot of work. We can start by finding and amplifying as many instances as possible of people doing real work in real communities to make their worlds better. We can commit to finding, and believing in, different stories—the ones that make us realize a different world is possible, and then making it probable.

*“We” is a word I frequently stumble over and have begun to specify more clearly since this piece was first published. Fundamentally, I think English just needs a different word, or a few different words, to bring about more nuance when talking about societal thinking that shouldn’t be characterized as “us vs. them” while also finding ways to make it clear who is meant by every varied instance of “we.”