If you’re new here, welcome to On the Commons!

Here, we explore questions as varied (but related) as: What is the difference between attention that fractures us and attention that restores? What role have three 15th-century papal bulls served in the “claiming” of land worldwide by Christian peoples of European descent, and how have those claims evolved?

New writing! Elementals, a new anthology from the Center for Humans & Nature, is out now: “The Elementals series asks: What can the vital forces of Earth, Air, Water, and Fire teach us about being human in a more-than-human world?”

I have an essay titled “Trespassing” in Air, alongside stellar writers like Báyò Akómoláfé, Ross Gay, and Roy Scranton. Other volumes include writing from Robin Wall Kimmerer, Andreas Weber, Tyson Yunkaporta, Sophie Strand, Joy Harjo, and many more. As with their previous series Kinship, this anthology brings healing and guidance to a world sorely in need of both.

This essay, on the legal question of where ownership originates, and the perspective gained by thinking in geological time, was originally published November 11, 2022.

One mid-morning on a bitterly cold November day, I was sitting at a table with my younger sister, her two little girls, and my younger kid. We were staying at a rented Forest Service cabin in Montana’s North Fork valley, no internet or electricity or running water, having recently cleaned up from breakfast and playing an interminable game of Unstable Unicorns.

I glanced up from my hand with the two “Neigh” cards I kept forgetting to use, when I lost control of words and patted my kid on the arm enthusiastically several times before managing to say, “There’s a fox on the porch!”

My kid had been hoping to see a fox in person for ages and thought I was joking, but no. She was right there looking at us through the window. I’ve seen a number of foxes around our town, but my kid somehow always misses out.

We all put our cards down and padded from window to window as the fox tracked around the cabin, watching her until she disappeared back into the woods.

One of the most famous and pivotal property law cases in U.S. history, the 1805 case Pierson v. Post, involves the hunting of a fox. The legalities of that particular case have staying power for a reason. They hinge on the question of what grants ownership: labor or possession? Was it Post, who was hunting the fox, or Pierson, who actually killed it, who owned the animal in the end? New York State Supreme Court reversed a lower-court decision in Post’s favor and granted ownership to Pierson. The written decision reached back through centuries of legal thinking, drawing even from the Byzantine emperor Justinian I.

Law students—and people like me who study too much about this stuff—can get hung up for ages arguing about the ownership philosophies of William Blackstone and John Locke and whether it was the labor of the hunt, or the person who had physical possession in the end, that determined ownership. Labor and possession being two keystones of property law.

Yet rarely is it asked: What about the fox herself?

How can ownership really be debated or discussed without considering whether every entity has rights in and of themselves? To exist, to wander freely, to sniff around a porch for food humans might have neglected to store. To decide they don’t want to hang out and watch those said humans play Unstable Unicorns.

The five of us were staying at this cabin in my usual run-away-from-election-news routine. I have an unfortunate emotional reaction to elections. I’m sure it’s not uncommon, but it’s exhausting and also completely useless to be refreshing news every few seconds, tracking outcomes to events that I have zero control over. A few years ago I started renting cold, electricity-free, mouse- and packrat-loved cabins far away from internet service over election days. It’s something I hope I can keep doing as long as Montana, where I live, still has early absentee voting widely available. Which might not be long.

When we drove up to the cabin, my sister said, “Are you fucking kidding me?” in response to the stunning view, and I said, “When do they light the beacon fires?” because it really did look like the beacon-lighting scene in the movie version of Lord of the Rings. This is from two people who live barely an hour’s drive away and grew up here. You’d think we’d be used to the beauty. You’d be wrong.

But I don’t just engage in this ritual so that I can get away from it all and admire the view. I persist in it because I want to spend that day reminding myself of why I care. I’m not interested in politics because I’m into politics. I’m interested, and emotionally invested, because I care about this world we all share, these ecological and social and spiritual commons. Going away to a silent river valley, spending all night feeding the wood stove every hour because it’s well below freezing, watching Sun rise over the mountains, being surprised by a fox—these things remind me why I volunteer in my community, why I encourage people to attend school board and city council meetings now and then, why keeping places like the North Fork free from too much human development is important, why the political bent of my home county breaks my heart all the time, and has done since I was a teenager.

It also reminds me that my heartbreak isn’t even a noticeable microbe in the span of geological time.

A few years ago we visited Zion National Park in Utah, another place of surreal beauty. I stopped on a trail to observe the facing cliff for a while, so tall it felt unreal. All that orange- and red-tinted rock, and somewhere deep down in the face, a single, narrow band of black. How much time did that band represent in the hundreds of feet of stone surrounding it? A thousand years? Ten thousand? Everything that happened in a span of time far beyond humans’ ability to grasp, pressed into that one bit of different-colored rock, a tiny note for future observers to see: Something happened here. For millennia. And yet in the vastness of geological time it barely left a mark.

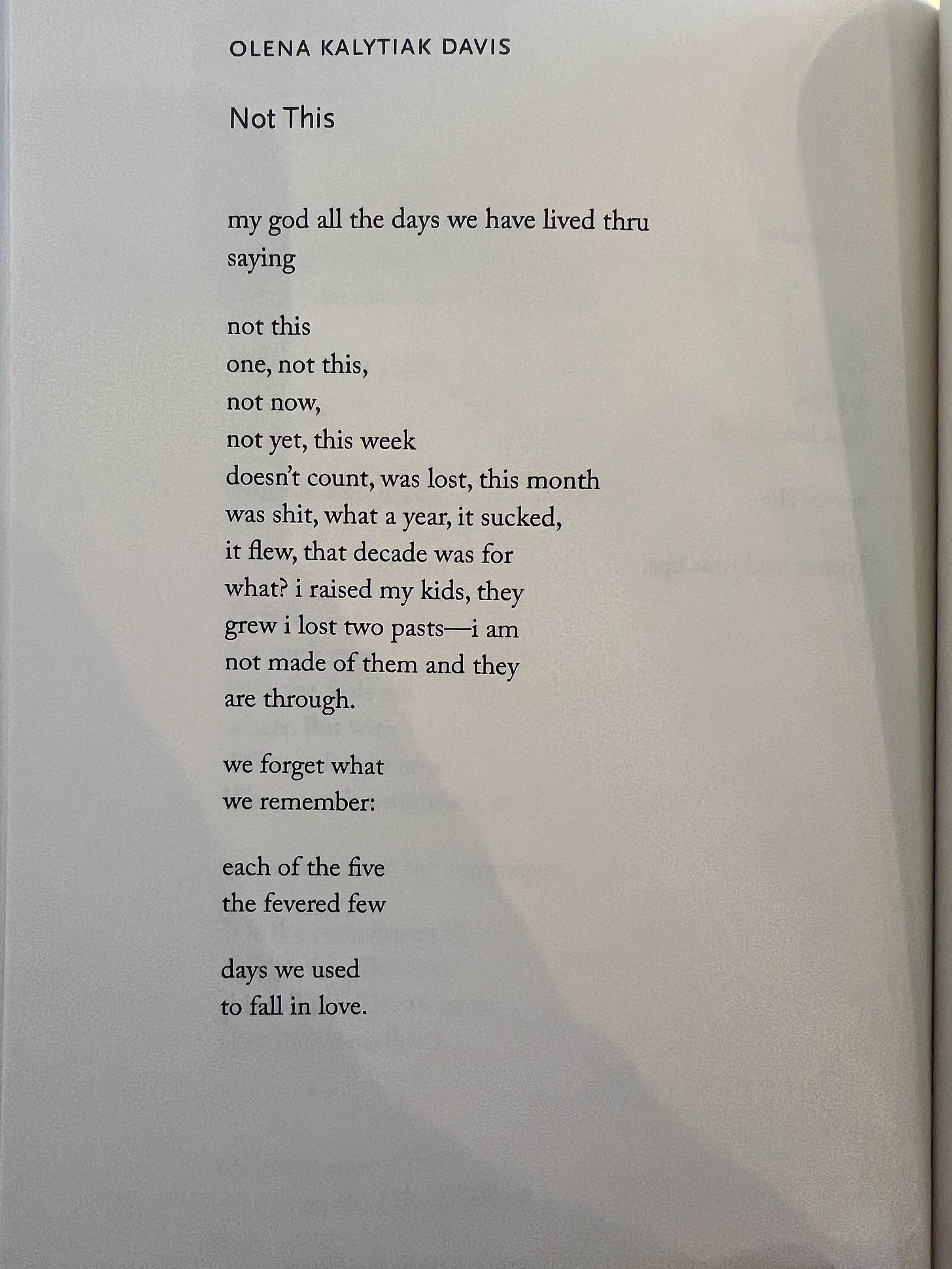

Several hours after the fox left us, alpenglow from the sunset hit the snow-covered peaks of Glacier National Park (pictured below), looking deceptively like a sunrise, and barely forty-five minutes later full Moon rose behind them (pictured at the top of this post), covering the entire valley with the kind of unfiltered indigo sky-light I sometimes forget exists, and we all stood in our pajamas and watched it, our breath spilling out into the frozen air.

I thought about the fox’s visit, and Pierson v. Post and the question of property, and how long ago it was that some humans decided to claim ownership over others—water, women, wildlife, and seeds; our relationship with those contain the ancient genesis of ownership, I continue to believe—and then create justifications for such claims through centuries of philosophical, religious, and legal argument.

What could change if we inverted that relationship? If we started from an assumption that all beings own themselves, that every being has agency and choice?

Our lives are so short. The events that shake our worlds so brief, against the timespan of stone. No matter what is forgotten of these times—eventually, everything will be, and everything for hundreds and thousands of years on either side of us, even foxes and Unstable Unicorns—it still matters how we care for one another. How we practice kindness, how we love, how we watch Moon rise and whom we share it with.

The joys and the pains are not everything, but they are not nothing.

In the comments on the original essay, Charlotte Hand Greeson shared a link to law professor Ann Tweedy’s then-recently published poem from the point of view of the fox, “Pierson v. Post’s Unheard Voice.” You can download the full poem from that link—it’s beautiful—but here’s a taste:

“I learned since that the man on the horse and the man on foot quarreled about the right to kill me, had a third person decide. . . . . . . Students still study the story but give me not a moment of their time. I am the invisible focal point. . . . . . . You are right to think that, alive, no one could own me. That’s the only true part of your story.”

Sunset’s alpenglow on the peaks of Glacier National Park