A Walking Life starts with what mainstream news sources call a “refugee crisis.” I don’t like that term any more than I like the term “migrant”—I love the richness that words hold, the worlds they carry, but their ability to flatten is equally powerful. These are shorthands that limit how we think about one another: a crisis of refugees, or a crisis for people who’d been forced to become refugees?

The story was one that dominated news headlines in 2015: people fleeing war in Syria, on foot, stuck for a time in Hungary before being allowed to cross the Austrian border and on into Germany. Vienna, Austria-based BBC reporter Bethany Bell, an old friend of mine, was reporting from the border, where she sent me pictures of the piles of abandoned shoes “worn-out and inadequate to the monumental task they were being given,” I wrote. “In between interviewing refugees, Bell took pictures of bedraggled shoes and a prosthetic leg abandoned on the pavement. Another pile of donated shoes waited to be put to use.” In her interviews, she found an unexpected sense of hope, and, she told me,

“‘for me there was something deeply human in it. For all the things we create for ourselves, the homes we build, the lives, sometimes you just have to walk away.’

Walking is both our first step and last resort when fleeing war or persecution. A refugee doesn’t have the luxury of restraining his step with respect to political margins.”

Journalist Kathleen McLaughlin wrote recently about the line a lot of us living in . . . let’s say “politically challenging” places hear on a regular basis: why don’t you just leave? Which not only, as she points out, ignores financial and other constraints, but also, as she also points out, ignores the reality that harmful or violent politics don’t stop at borders.

The spectrum of who flees, who’s forced out, who’s being put at grave risk by staying, and who stays to fight no matter what the cost, is vast. It’s determined by factors that accumulate and pull on one another and is, in the end, beyond anyone else’s individual judgment. Not everyone can leave. Not everyone is allowed to stay.

All I can personally say is that the story of whether or not one leaves a home, and how, and what level of choice is or is not involved, is the story of humanity. It is in this particular story that my writing about walking and my interest in private property intersect most profoundly, and in ways that often surprise me.

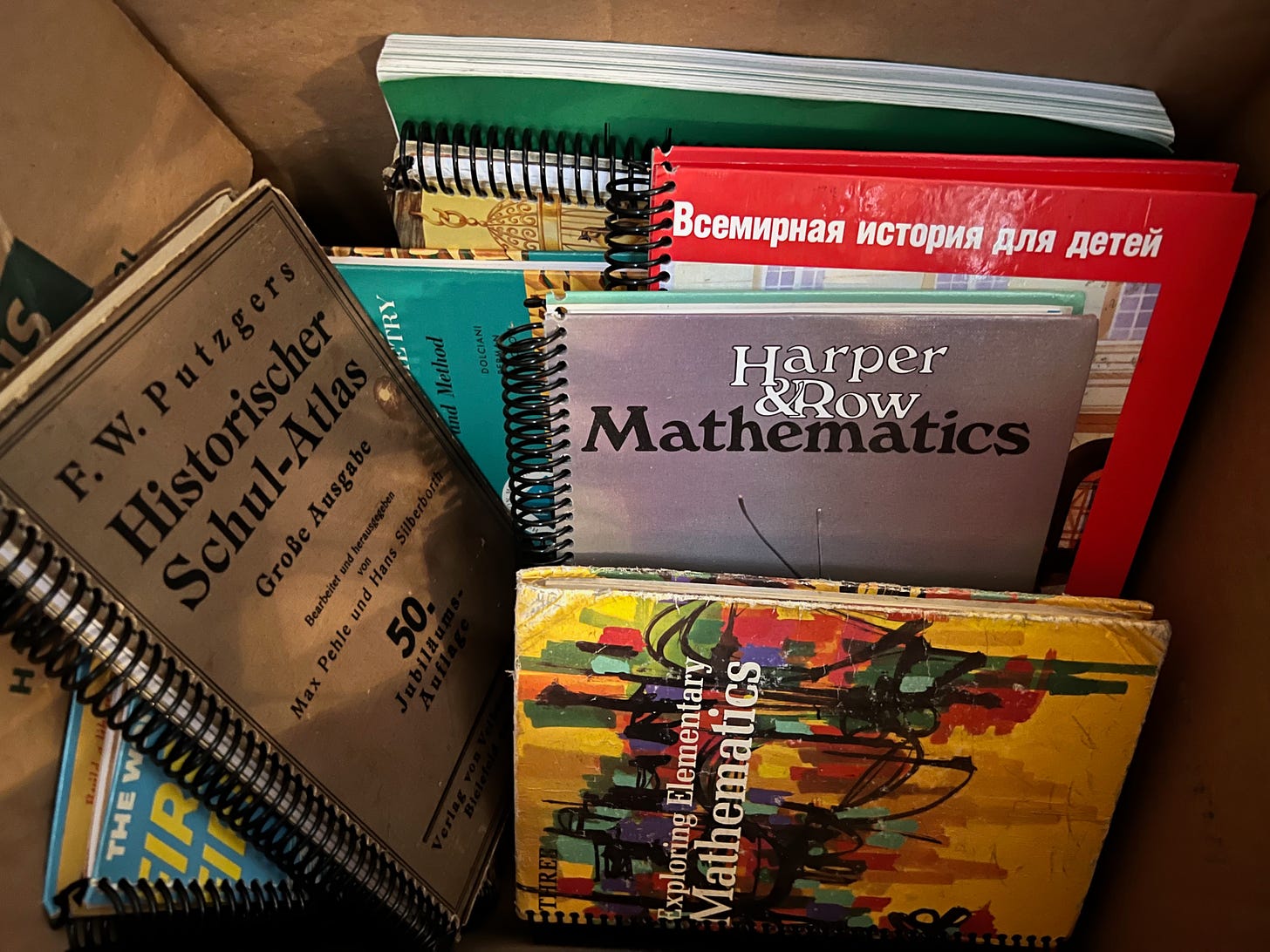

A couple of weeks ago I came across an article some of you might have seen, about a database compiled by The Atlantic of the books used to train generative-AI systems. I figured my book had to have been used, along with the 20 years’ or so worth of writing I have online, since last winter my spouse put my name into ChatGPT and said, “Look! It can write an essay in your style!” (This conversation did not go well, though I think we eventually got to the point of me being able to explain why the last thing in the world I want is a machine to do my writing for me, especially one that’s stolen my work to do so.)

Sure enough, A Walking Life is in the database. It winded me a bit to see it verified.

To be clear, the copyright issue is the least of my concerns. If you want to go to a local library and photocopy every page of A Walking Life and pass it around to people who want to read it, I’d actually be thrilled. That is, after all, how my father and his family read Solzhenitsyn in the Soviet Union, though photocopiers were highly controlled and only in government offices and a bureaucrat risked his life to get those stories out into regular people’s hands. The more copies of my book are purchased, in whatever form, the happier (theoretically) my publisher is and the better chance I have of selling them or someone else on another one, but it’s far more important to me that people read it than that those reads show up in the graph provided for me in my publisher’s author portal.

It’s a completely different thing to have a multi-billion or -jillion or whatever-dollar company steal my work and then use it to both make more profit for itself, and to put other writers and artists out of work.

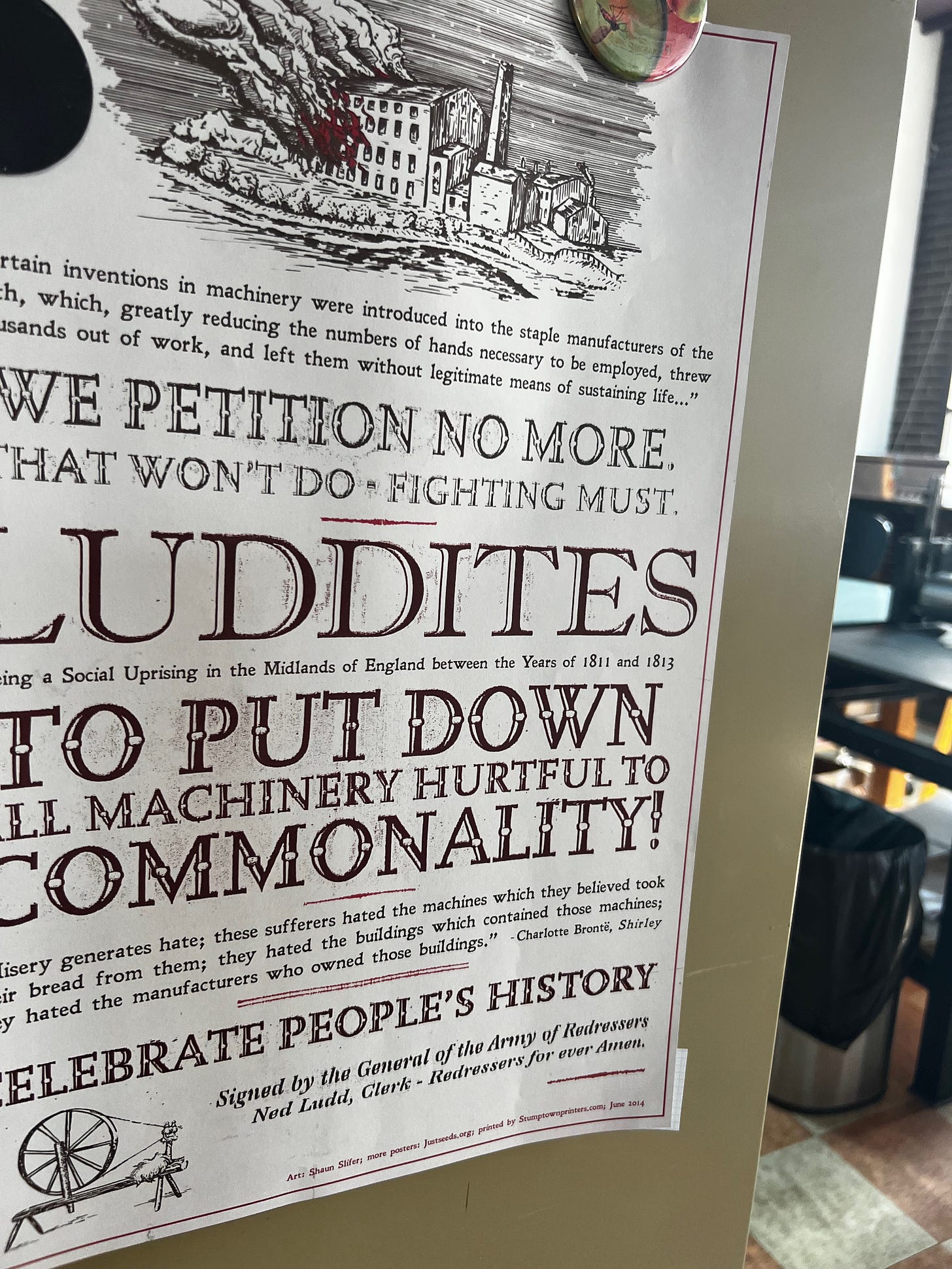

It’s also impossible to disentangle complaints about AI and other digital tech from the long history of technology being used to deliver more profits to a few, steal masses of people’s labor, and provide lower-quality services and products to people paying for them, along with building unjust and destructive structures that humanity and the rest of life simply have to live with going forward as best we can. Roads, highways, and automobiles are the examples I usually bring up but there are plenty of others. In A Walking Life I wrote about the Luddites, who are usually characterized as anti-technology but weren’t that at all. What they objected to was being forced out of their jobs—with no compensation or safety net—by machine adoption that made more money for the factory owner while also producing shoddier products.

Luddite poster art from Justseeds.org, spotted in a Butte, Montana, art gallery last summer.

It’s not about whether technology exists or not. It’s about how it’s used, its effects on people and ecosystems—the energy and water consumption of AI and data centers is absolutely staggering—and whether its role in the world is to contribute to life’s well-being or make it worse.

“The planning structure always fits well into the needs of the powerful,” said physicist and technology philosopher Ursula Franklin in a series of 80s-era lectures (undying gratitude to Jake for sending them to me; they’re amazing). “It rarely fits well into the needs of the powerless, and that is where the struggle sits.”

She gave that lecture long before talks of artificial intelligence became rampant, but whether we’re talking about AI, highway systems, railways, or the mills and machines that powered the Industrial Revolution, her questions hit home:

“Do people matter, or are people in the way? The technology will come once we make the decision whether indeed people matter or whether they are just in the way, and you design more and more stuff to make more and more people unnecessary, unneeded, and redundant. Don’t ask what benefits. Ask whose benefits, whose costs.”

The theft of my book, which took years of research and writing to produce, hasn’t done anything to improve my life, and I doubt it has anyone else’s, but it’s certainly contributed to someone acquiring just that bit more wealth, which can then be used, as wealth always has been, to tip the scales of injustice a little bit more in their favor. My cost, their benefit. That is what enclosure is, both historically and currently: taking that which was in use by all or already belonging to someone in one form or another, and making it your own for the purposes of private profit.

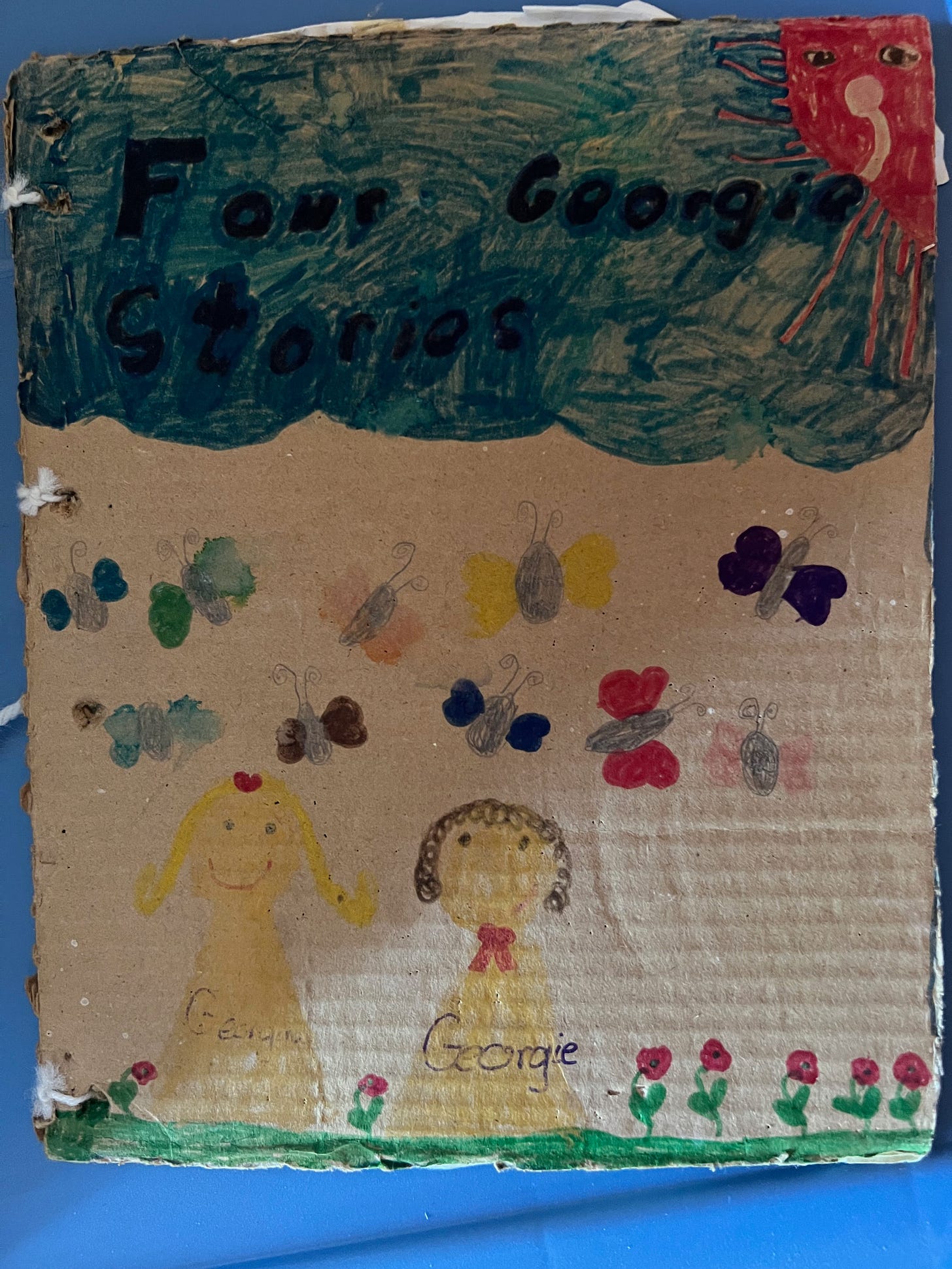

Neither I nor any other writer or artist has been given a choice in the matter, nor can we disentangle ourselves from the systems we’re being frog-marched into, not unless we give up creating entirely. And I can’t think of a single writer I know who would even consider that. We create because we can’t help it, because it brings us joy, because to not do so would be to flee one of the things that makes us feel most alive.

“There is no reason,” I wrote in A Walking Life,

“why our online lives can’t be used as a tool to enrich our restored communities, no reason why we can’t recover from the flu with some good friends bringing us soup and others bolstering our spirits through Instagram.”

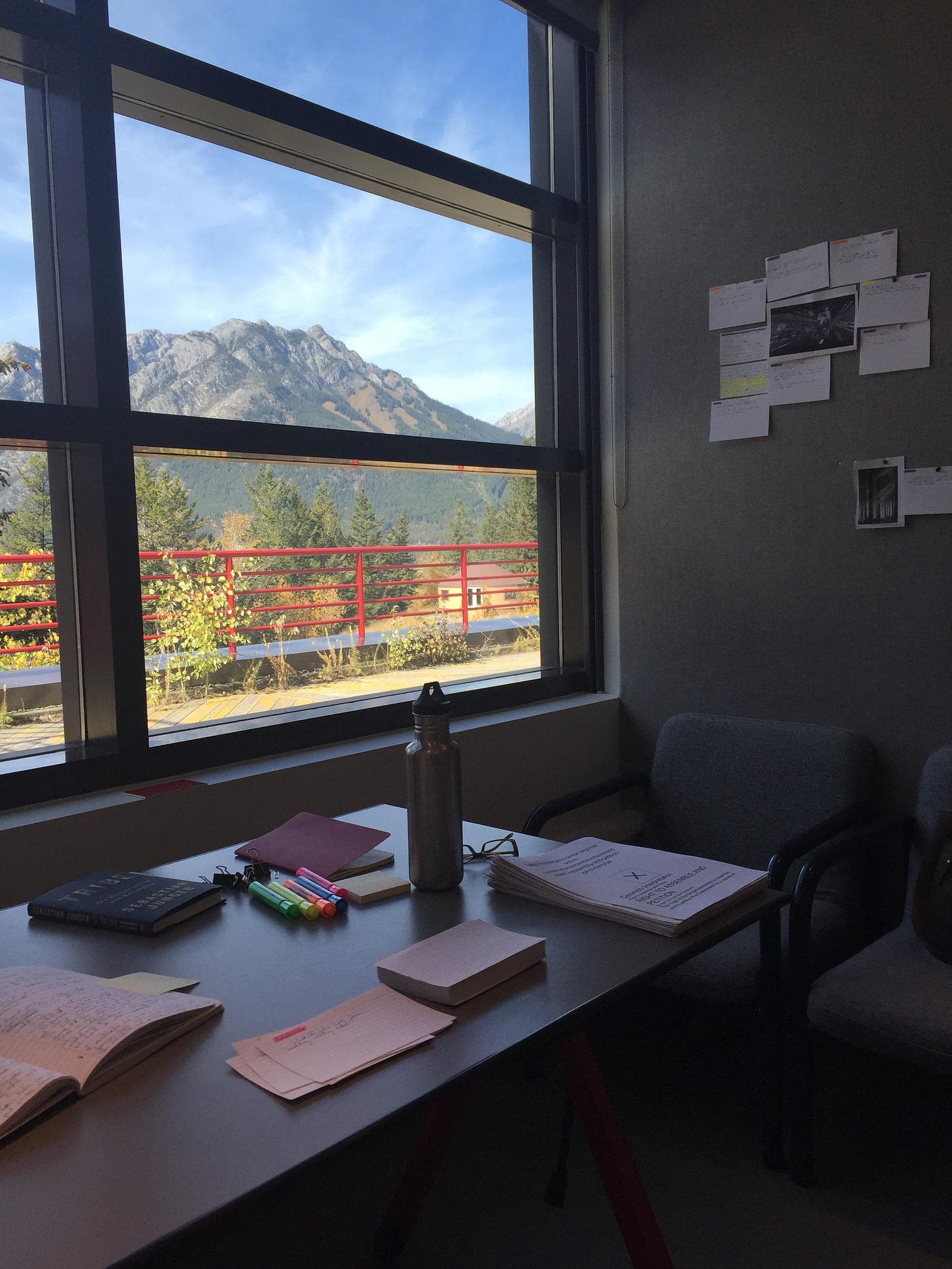

Which, in my feverish and brain-fogged state when I came down with Covid last week—a week after getting a third booster shot!—I was delighted to notice was exactly what happened: A friend came by and left a jar of soup and some leftover huckleberry galette by my door. My brother-in-law offered to drop off more turkey broth. Another friend brought me groceries on her way home from work at the rail yard and included a bar of nice chocolate she knows I like.

And then a friend online, whose newsletter Berkana is one of the most beautiful and thoughtful on Substack, sent me a short video of someone making turmeric chai that was so soothing to listen to and watch I let it loop several times before realizing it was something I could actually do (the brain fog of this virus is very, very real for me). So I made some and drank it and did so again in the middle of the night when I couldn’t sleep, and you know what? I felt better the next day!

A Walking Life is about a lot of things, but at its core it’s about being fully alive beings on a fully alive planet. Walking leads us into every one of these subjects because walking is how we evolved. From the perspective of evolutionary biology, it’s what makes us human. And it’s what can shine a light most clearly on the barriers that have been placed to prevent our full exploration of that humanity.

The Authors Guild, of which I am a member, has filed a class-action lawsuit against several of the companies who’ve used published books to train AI. I gather some of the basis for the complaint is that the content was scraped from a site of pirated works. I’m curious where the lawsuit will lead, though it’s currently only for fiction and I’m not going to get too hung up on its potential. For nonfiction writers and others not immediately affected by the lawsuit but whose work is in the database, the Guild encourages us to write letters to the companies involved and provides a form for that purpose.

Which honestly made me laugh. I appreciate the thought but have better things to do with my day than beg any one of these enormously wealthy and powerful people to please not steal my work to make themselves richer. I can spend that time making more turmeric chai, for example. Or sewing up the hole in my kid’s blanket. Or writing a letter to my county commissioners about their gutting of the county library system, which I doubt they’ll care about but at least they’ll read (maybe). Or I could go for a walk.

These huge, systemic problems can’t be solved by piecemeal approaches, and in any case my focus is on the deeper structures that make the harms possible. Technology has been used both to improve human and non-human life for millennia, and it has been used to control and destroy it far more often. It depends on who benefits, who pays the costs, and who decides.

Perhaps most damaging of all, it’s been used to determine what we think we can imagine: a way of being in the world and living together that’s not determined by the control, power, and ownership of a very few. A world where food, shelter, health, soul-fulfillment, relationships, and even the joyful gifts of creativity are not dependent on tricking us into thinking we can only succeed in competition with one another.

I want us to unburden ourselves at the very least of restrictions around what we conceive as possible, and to contemplate a world where leaving means to wander freely, rather than being forced to flee—whether on foot or in the worlds of our own imaginations.

Someone’s been updating the No Trespassing signs on the fencing around the rail yard in town.