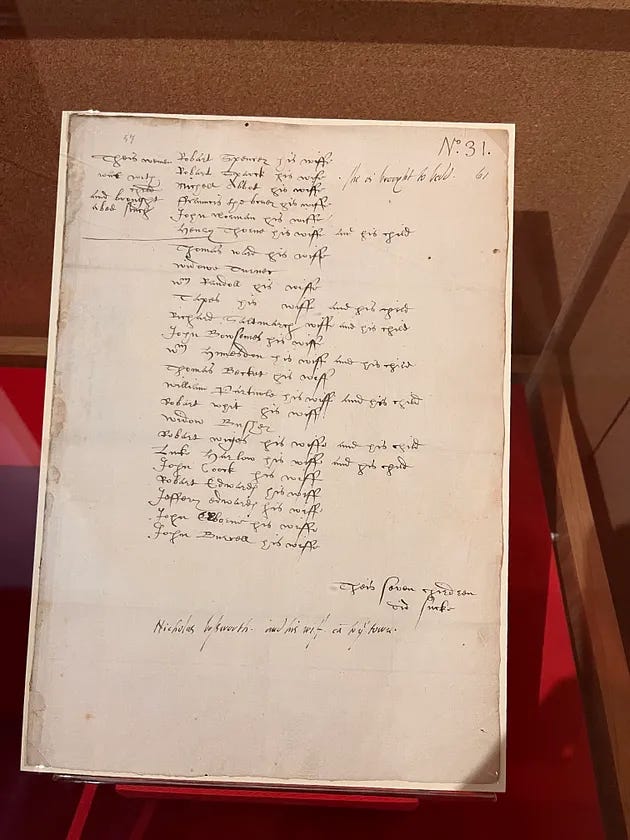

My mother sent me a birthday card years ago that I have put above my desk everywhere I’ve lived since. On the front is a reproduction of a painting by Deborah DeWit Marchant, dated 1994: a woman, brown-haired and pale-skinned like me, is sitting in a booth at a diner, next to a window. On the table in front of her are an empty plate with what looks like the remains of pie, a glass of water, a cup of coffee, and an open book. Her left hand rests against her face and she is reading. The street looks wet with recent rain. The woman’s hair is even braided back, as mine almost always is.

The painting is titled “The Artisans Cafe.” There’s a sense of peace in it I’ve always loved, a sense of allowance—this woman can sit there getting lost in a book, no other demands on her attention for at least a little while.

For years I’ve looked at that picture with both longing and an internal struggle. It speaks to me of the kind of permission to rest that too few people in this life, including me, feel they can allow themselves. I’ve been caring for others since I was four years old, when my younger sister was born, and when I look at that picture I see a moment for myself when everyone is fed and occupied, all the dishes are done, and the floor swept, the laundry folded and put away, the endless tasks of housekeeping and people-caring soothed and calmed and, for the moment, finished. Complete. It’s a moment that never comes.

Maybe it’s the pie plate that gets me. This woman has eaten, and has time to enjoy her book, and her coffee while it’s hot, and doesn’t even have to wash the plate. What a luxury.

I long for the moment in that picture nearly every day. It takes a lot of mental effort to give it to myself once in a while, breathe into the moment, any moment, even while the laundry remains overflowing and last night’s frying pan is waiting to be scrubbed and the peas need picking and the strawberries weeded and forms filled out and the bank account stressed over . . .

In the original draft of this, I followed that line with a list of all the things I’m behind on, everything that keeps piling up, but those details aren’t important. Each of you has your own list, your own burdens and worries and piles of laundry.

None of it will ever be caught up on permanently, much as I long for that moment, and in the midst of it all is my own work, which has been intensive for a while and will be for a few months more. An essay for this newsletter about the conflation of wealth and power that I keep needing to cut down (really, there’s no need to quote every book on this subject I’ve ever read but it’s hard, and do you really want to know exactly how Aristotle advised overthrowing oligarchy? yes, probably), essays for non-Substack outlets, and a lot of editing. A lot of editing.

Over the past six months I’ve been helping my friend Kathleen McLaughlin, longtime journalist and author of the fantastic book Blood Money, with a new anthology of essays by Montana writers she’s putting together for University of Oklahoma Press. It’s been a project she’s been shepherding for over two years and it’s finally taking “holy crap this is real” shape. I have an essay in it, but far more interesting to me is that I’ve been working with over twenty writers copy editing and helping develop their essays about Montana. In over twenty years of copy editing, which I mostly do for K-12 textbook publishers, it’s one of the most satisfying and challenging projects I’ve ever worked on.

It’s interesting being immersed in this editing just at the moment when what is marketed as artificial intelligence—but LLMs, or large language models, are not in fact anything of the sort, not yet—is being pushed as capable of taking over work like mine and I wonder, between rounds of essay edits, if I should take up the manager of the local tire shop on his persistent job offers. That job comes with health insurance and in America that’s far more precious than gold.

There are many levels to the speed of this technology’s adoption that are worrisome but out of my control, from people’s willingness to believe it truly is revolutionary simply because they’re told it is, to a complete bypassing of the reality that most of these systems are built entirely on stolen labor and stolen work—my book is among thousands used to train the LLMs with neither compensation nor my permission—and deployed not to improve people’s lives but to further bloat tech companies’ profits, to the deep, disturbing willingness to withdraw the possibility of creative work (much less income for it) from human beings who sorely need it.

A subscriber here once recommended this post to me, by science fiction and fantasy author Catherynne M. Valente, about artificial intelligence and creativity, that I’ve hung onto, while watching people who, for various reasons, justify the use of a product built on stolen labor and being used to replace the creative work not just of writing, but of editing:

“It can and will get ugly. But oh my god, people won’t stop writing or creating or performing, and they won’t stop coding, either, not the ones who love it and are passionate about it, certainly not because AOL Instant Essayist can, too. That shit is compulsive. From hands on a cave wall to these words on this screen, we cannot stop trying to express ourselves, and if one thing about our dumbfuck monkey dance on this call of salt will never change, it’s that. The unending plaintive scream of people trying to connect, to be heard, to be seen, to be known, to take what is inside us and make it manifest on the outside. . . .

Take away art and we’re going to art harder just to spite you.”

It’s also a really funny essay (while managing to be both slightly depressing in its realism and also empowering in its “fuck you we’re going to be human anyway” manifesto), so I’m going to quote another paragraph just because:

“This is not the optimistic part of the essay. Sorry. This the god dammit we spent literally all of science fiction telling you not to do this can you actually not for once part of the essay. Oh you’re definitely doing it anyway? And shoving me in my locker afterward? Perfect.”

For those who’ve never done it, this might be hard to believe, but editing is at least as creative as writing is. It is art. There is something almost indescribable about helping a writer tell their story or find how to say what they want to say in the best way possible, and in the way that is truest to who they are. It’s psychology and architecture, sociology and tailoring. It’s working with live wires of human storytelling all the damn time.

A writer I used to be friends with once told me that he thought my work as a copy editor simply involved “fixing commas and stuff.” I laughed, but was surprised at his assumption, since I figured he had to have worked with copy editors on his own writing once in a while. I do fix commas, true, but it’s a very small part of my job, which is far more about communication and storyweaving than it is about grammatical rules—which I know well enough to, frankly, not care. At least, not unless I’m being paid to. I’ll never correct your typos, unless you want to pay my hourly rate.

Copy editing is, for me and the copy editors I’m friends with, the people I respect, something far more in-depth. Something vibrant. It’s working with language at the level where it lives, before it gets pinned down in a dictionary like a butterfly specimen on a corkboard.

This really came home to me working on this recent project. So many writers, each with their own voice, style, strengths, and stories to tell. Editing is never just working with words or narrative; it’s approaching that narrative as an animal whom you have to get to know before touching. That animal could be affectionate, happy, traumatized, wild. Anything. The animal is alive and individual, their own self. That’s the point.

It’s working with who the writer of that narrative is, and the readers they want to reach. Sometimes, sadly to me, that means accepting when a writer is allergic to revision and balks at editorial feedback, meaning I only do the bare minimum. Frustrating, especially when there’s talent and potential, but I can’t force people to do their own stories credit. I just accept that they don’t want to know their work any more deeply than they want to know themselves and move on.

Other times, it’s the delight of working with someone who’s never published before and is eager to learn how to bring the best out of their own story in their own voice; or the delight of working with longtime, professional writers who feel the same. There are copy editors who will dictate to writers how to shape their story, but it makes me happy not to be one of them. It’s more fun.

This anthology project has eaten up an enormous amount of my time and energy over the past six or so months. It’s reminded me why I almost never teach or lead workshops: giving feedback in the way I do comes from the same creative place my writing does. I give of myself to other people’s work the same as I give of myself to my own writing, or to my kids, and I have to be careful with that. A couple of times I told Kathleen I had to take a break because my creative well was empty, and since she was of course doing even more work on the project than I was, she understood.

But it’s been far more of a gift to me. In the midst of a lot of personal and global turmoil, it has been a sheer pleasure to challenge myself, to be part of something I think is valuable and important, and to work intensively with such a large and varied group of writers, to be reminded that each one of them is an absolutely unique human being. As we all are.

It’s been both creatively fulfilling and soothing to my humanity—with each exchange and round of edits with each writer, with email conversations that veered into moments of shared experience and running jokes in their essays’ comments, I was reminded that there are no seething, personality-free masses of humanity, only people each with their immediate and intergenerational traumas, their struggles, hopes, memories, and battle-scarred heart.

Yesterday morning I woke up to the sound of a sandhill crane passing by, making me think of a few weeks ago when I heard my first of the spring as I waited in line at the tire shop before dawn to get my winter tires switched over and wondered if my ten-year-old car with 200,000 miles on it can handle another decade.

And earlier this week I came back from a self-guided Montana history trip with my younger kid (who’s been homeschooling this academic year) to meet the lilacs at home just beginning to open, and the two resident hummingbirds back in the caragana bushes. The tobacco plants and tomato starts thriving under the grow light my brother-in-law gave me, and the onion sets accusing me silently of neglect while the sweetgrass is thriving.

That night I stayed up to watch the full Moon rise in the southeast, an eerie green-blue glow through the night’s slight fog, the western sky still darkening from Sun who sets far too late this time of year for my taste, lover as I am of the cold and dark of winter.

It was, I’ve heard, a full Moon in Scorpio, a Moon for letting go, a release of what no longer works in our lives. I’ve got plenty of that, I thought, and hoped the murky moonlight would help some of it dissipate.

I have a new editing project starting just as this other one is finishing. It’s a book by someone I’ve worked with before on her audiobook, which I’ve often recommended, about algorithms and bias. She’s a roboticist who worked for NASA on the Mars Rover and is one of the smartest people I’ve ever had the good fortune to know in this life. My creative editor self is excited to immerse in that work.

Her book? It’s about the promises, pitfalls, and prejudices of artificial intelligence, by someone who knows these technologies better than almost anyone else—and, unlike many of us who criticize them, loves them while being clear-eyed about their flaws and risks.

Talking about this project with her brought me back to Ursula Franklin’s book The Real World of Technology, based on her talk in the 1980s that was recommended to me ages ago by a subscriber here and has become one of my touchstones since then.

“While we should not forget that these prescriptive technologies are often exceedingly effective and efficient, they come with an enormous social mortgage. The mortgage means that we live in a culture of compliance, that we are ever more conditioned to accept orthodoxy as normal, and to accept that there is only one way of doing ‘it.’”

Enormous social mortgage. What of our future freedoms and choices do we give up with every unquestioned technology adoption? Who else’s choices and freedoms do we strip in the process without their consent?

In times of darkness as well as times of rapid change, having clarity can feel almost impossible. It’s one of the reasons that I wrote before last year’s U.S. presidential election that one factor many people were missing was keeping the right to protest at all, to fight back, something that is currently—and unsurprisingly—quickly being criminalized. What kinds of choices can you make when the rights you thought were foundational, at least in theory, are being broken up and carted away?

There are at least as many answers to this question as there are human beings alive at any given moment. My own is to look at my Russian-Jewish grandparents and the kinds of choices they made living under the authoritarian dictator Joseph Stalin.

But it’s valid to look also, I think, to that unique human gift of creativity. The messy, tangled, most often unproductive and unprofitable, process that has been somehow fundamental to the history of our entire species, across the planet and over hundreds of thousands of years. One of the answers to how one remains free is—thank you, Catherynne M. Valente—to art harder.

Until all the children in the world live without fear of hunger, violence, oppression, or abuse and every border is marked only by a tree, a greeting, and a bit of cultural orientation, claims of technological progress are, for the most part, mirages obscuring accumulation of wealth and profit. (I’m not talking about developments like vaccines. Vaccines are great, as are many other technologies. But technological “progress” is not the unmitigated good it’s assumed to be—see the entire century of building a car-centric world and the attendant pollution, severed communities, and human health consequences.) They might be developments most of us have no control over, but we can choose to keep our humanity as intact as possible.

I see no reason to give up writing or editing, even when so many believe the marketing hype that says LLMs can do those tasks just as well. I don’t, frankly, care whether they can or not. I care that people believing it’s true will probably eviscerate my ability to make a living doing something I love, but that won’t stop me from doing it. Storytelling, as I’ve written before, is for me paired with walking—a fundamental human experience, core to who we are as a species. I don’t intend on giving that up, even if I need to get a job at the tire shop to pay the rent and feed my kids. It’s not a bad job and the people there are nice.

Editing and writing are, for me, represented by that old birthday card above my desk. Every word considered or line scratched out in my notebook, every minute sitting with a writer’s essay and trying to sink into what it is they’re truly trying to say, and to whom, is a moment of rest, clarity, and the ineffable spark of insight. It’s life, interwoven with the hummingbird outside my window and the river that runs through town and the heartaches and losses and beauty of human experience. It’s connection to whatever it is that holds it all together—holds us, all, together.

It is my chance to live in the Artisans Cafe whenever and however I can.

My kid and I stopped in Missoula on our way home from the history trip, took a wander along the big-shouldered ponderosa pines of Maclay Flats and were rewarded with fresh beaver chew. Every moment of our lives is a struggle between contributing to technology’s social mortgage, which we can’t always escape, and . . . this.