“Oligarchy is based on the notion that those who are unequal in one respect are in all respects unequal; being unequal, that is, in property, they suppose themselves to be unequal absolutely.” –Aristotle, Politics, 350 BCE

My last year of college, I applied for a coveted internship at a relatively prestigious literary magazine in St. Paul, Minnesota. When the acceptance arrived, I was excited for all of a few hours.

Then it came home to me that the internship—as is the case for most internships—was unpaid. The editor who’d interviewed me seemed surprised when I called later to ask about the possibility of even a small stipend.

It was the final semester of my final undergraduate year. I’d taken the previous semester off of university and moved back to Montana to be an adult around for my younger sister, who, at fifteen, was in high school and living for the most part alone (long story). Before that, I’d been working up to five different jobs at a time to support myself through college.

The week I was offered the internship, I went for a long walk with someone I’d been friends with since our first confused, heady days of freshman year. He bought me a sandwich and listened to me angst about whether or not I could afford the money—and the time—to work at a job I’d probably enjoy but for which I wouldn’t be paid.

It wasn’t possible, I already knew that, and at the end of our walk we parted at the door of the family diner where I’d been working as a waitress the previous year—a job I took because making tips got me a lot more rent and grocery money than the coffee shop I’d worked at my first two years of college.

So I turned down the internship and waited tables instead. Every now and then another waitress and I got together at her apartment to paint our nails and watch Xena: Warrior Princess and I tried not to think about who got the assistant editing position I’d been so excited to be offered.

The advantages of wealth and privilege get mentioned a lot but not usually with much substance. I’m not sure how many of us truly understand how wealth accumulation turns into power, influence, and status—the literary world is only one small example of how the financial freedom to work for free gives a person entry and connections in all directions, from publishing opportunities to awards and grants to the strange situation that’s evolved in the past couple decades where “writer” is in many places equated with teaching workshops almost more than it is with publishing, or even with the act of writing itself.

But this isn’t only about the writing world. It’s about money, and power, and their feedback loop.

It took me months to even sit down to write a first draft of this essay because the subject bumps against one of my own failures of imagination: it’s very hard for me to understand how millions, or even billions, of people don’t understand how accumulation of wealth leads to accumulation of power, and how the combination leads inevitably to large-scale human oppressions, environmental degradation, and almost every kind of injustice and inequality.

The combination of power and wealth has always led to the failure of societies, and in their current iteration are leading quickly to the failure of the human species.

In the month or two before the November 2024 U.S. presidential election, I picked up David Herszenhorn’s book The Dissident: Alexei Navalny: Profile of a Political Prisoner, about the Russian dissident and anti-corruption activist Alexei Navalny.

Navalny became internationally known after surviving an attempted poisoning, likely ordered by Russia’s top leadership, and then running for president of Russia against Vladimir Putin. But the core of his work was always about corruption. His investigations and fiercely productive blogging activity focused on business deals that benefited government officials, their families, their friends, their friends’ families . . . almost always at the expense of the Russian people and Russian land, whose natural resource wealth of oil, timber, and minerals was not-so-quietly but very quickly privatized by those already in power, for their own gain, in the years following the 1991 collapse of the Soviet Union. Those who benefited most from the privatization were, largely, either those who had held power in the Soviet Union, or people connected to them.

Vladimir Zelensky, an actor and comedian who was elected president of Ukraine after starring in a very successful comedy show about a teacher whose anti-corruption rant went viral, resulting in him unintentionally becoming president, came to fight internal corruption and the influence of Russian wealth and power as the real-life leader of Ukraine.

Navalny was most likely murdered for his anti-corruption work. Zelensky’s country was invaded in 2022 and continues to battle an army of Putin’s soldiers, many of whom were forced into fighting. I’ve heard plenty of stories of disobedience turning into forced conscription that I can’t even share publicly.

And in January 2025, the U.S. government faced, and quickly folded to, a hostile corporate takeover in which the wealthiest person in the world for months wielded the power to fire anyone employed by the government, from wilderness trail crew workers, to people monitoring clean drinking water, to core staff running the power grid of the entire Pacific Northwest.

Everywhere you look, a combination of wealth and power seems to be battling to control more of the same—and winning.

Of course I want to burn it all down. Don’t you?

The problem with that is, as I’ve written here several times before, whenever entire systems and structures are burnt down, it is nearly always those most at risk, those who’ve suffered most, who end up suffering more.

The accumulation of wealth leads to rule by oligarchy, but it also provides those with power the means to protect themselves from inevitable resistance, even mass violence, the French Revolution notwithstanding.

Whatever system arises from the rubble, those who’ve previously accumulated wealth usually have the means to maintain their power structures, or rebuild them all over again.

In his book Black Sea, Neal Acherson described the strange self-protective quality of wealth through the behavior of Polish nobles whose resistance to reform led to the Third Partition in the late 18th century and the dissolving of Poland as a country for 123 years:

“To the end of their lives, many of these Targowican barons failed to understand what they had done. They kept their vast estates, travelling now to St. Petersburg and Odessa rather than to Warsaw and Krakow. They had lost the political influence they had enjoyed in the old commonwealth, but to be appointed Marshal of Nobility in some Ukrainian county was not a bad substitute. . . . The fact that they themselves were secure and prospering could only mean that all was well with Poland too.”

To put it in more familiar terms: in the 18th century, the Polish nobles fucked around and everybody else got to find out.

In The Sociology of Freedom, co-founder of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) Abdullah Öcalan—who has been incarcerated in a Turkish prison since 1999, many of those years in isolation—tracked the question of power back at least 5,000 years, to the beginning of people’s ability to begin controlling and accumulating surplus “product”—food for the most part, but also other people’s labor.

Wealth, in his writing, is the ability to accumulate and hoard the resources that people need to survive, including food and work. Power comes from control over that wealth:

“The fundamental characteristics that have marked the central civilization from its very beginning and determined its character have remained essentially unchanged for five thousand years. . . . One characteristic that remains stable whatever the differences or forms adopted is the monopoly’s hegemonic control of surplus product. . . . We must take care to understand the monopoly. It is neither purely capital nor purely power. It is not the economy, either. It is the power to use organizations, technology, and violence to secure its extortion in the economic area.”

Much of the power in wealth is about who owns what, which translates into who controls and dominates what, especially land, water, food, and the right to pollute the commons we all need for survival. Vandana Shiva—who’s been working on seed and food sovereignty in India for decades—has in recent years reiterated what can never be said enough: “If you control food, you control people.”

The U.S. government’s determination to wipe out buffalo and destroy land relationships through iterations of theft so as to force people and Native Nations into dependence in recent history is proof enough of this (its goals in this respect are explicit and well documented); and if you read about enclosures of the commons over the past 800 years of British history, you’ll also run into plenty of examples of entire villages of people evicted and starving and forced into “jobs” for the first time because a few already-rich people wanted to get wealthier by raising sheep on land that was previously used and lived with in common.

To give just one example, Andro Linklater, in his sections on England’s enclosures of the commons in Owning the Earth, wrote:

“In a single day in 1567, Sir Thomas Gray of Chillingham in the north of England cleared off his manor no fewer than 340 villeins, cottagers, and laborers whose right to work their plots of land existed simply by tradition. Whole villages and townships were soon emptied—in Shakespeare’s county of Warwickshire alone, sixty-one villages were wiped out before the year 1500.”

These land thefts and evictions led to starvation and mass homelessness and criminalization of the same through anti-vagrancy laws and the right to enslave people found to be in violation. Those who were already wealthy had the power to take what they wanted, call it theirs, and justify the theft through philosophies and laws that placed rights of property—no matter how it was acquired—over the rights of people, and of life in general.

The long-term impacts of wealth—whether of land or wealth in other forms—accumulate intergenerationally, for far longer than most of us realize. A research paper co-authored by scholars with the Bank of Italy and the University of Bologna that tracked intergenerational wealth in family dynasties in Florence, Italy, from 1427 to 2011 challenged a common misconception that family wealth is usually wiped out within three generations. They found instead that the top earners of today are most often descendants of those “at the top of the socioeconomic ladder six centuries ago,” families who had been lawyers or members of elite trade guilds in the year 1427:

“Intergenerational real wealth elasticity is significant too and the magnitude of its implied effect is even larger: the 10th-90th exercise entails more than a 10% difference today. Looking for non-linearities, we find, in particular, some evidence of the existence of a glass floor that protects the descendants of the upper class from falling down the economic ladder.

These results are new and remarkable and suggest that socioeconomic persistence is significant over six centuries.”

The authors pointed out that the results are particularly remarkable when you consider the enormous social, economic, and political upheavals that took place in that region over those centuries, “and that were not able to untie the Gordian knot of socioeconomic inheritance,” a reality that they felt comfortable extending to similar countries in western Europe.

Ownership and wealth are far stickier and more resilient over time, even over collapsing societies, than most of us would like to believe.

And of course what security of wealth both comes from and translates into, along with power, is ownership of property—land in particular.

The weight of wealth and power is enormous. It sucks up life and resources, and seeks more of the same; it crushes people and feeds off their labor, and seeks more of the same. When it faces resistance, it responds by protecting itself. Maybe firing someone. Maybe abusing or even murdering them. Maybe invading an entire land.

The Roman Empire is one of the most well-known cases in point. “Empires entail ongoing costs,” political economist John Rapley wrote in Aeon about the Roman Empire. “The richer an empire becomes, the more it must spend to preserve that wealth,” spending more money on ever-shakier military campaigns and using up public funds to protect the security—and property—of the wealthy and powerful within its borders.

“Power,” wrote Abdullah Öcallan, “is not simply accumulated like capital; it is the most homogenous, refined, and historically accumulated form of capital.”

Power, in other words, is a manifestation of wealth itself. It is what wealth is for.

Given the resilience of wealth, the protective quality it gives to those who have it, what are we meant to do about the power it wields, power that causes an immense amount of damage and limits everyone else’s freedoms? What’s the answer, the solution?

There are two that I can see: the first and most urgent is to tax wealth, obviously. Prevent the kinds of massive accumulation of resources that lead to accumulation of power. Pretending that one doesn’t lead to the other, and that their combined strength don’t lead to oppression of most of the human population as well as destruction of much of the rest of the living world, is a fairy tale.

David Wengrow and David Graeber’s book The Dawn of Everything is partly directed at this problem, detailing societies across the planet over several thousand years and how they rose and fell and shaped themselves—or didn’t—around an awareness of the dangers of wealth and property accumulation. Those shapings, the authors wrote, determine everyday people’s security of three essential freedoms: “the freedom to move, the freedom to disobey and the freedom to create or transform social relationships.” Wealth accumulation—especially in landed property over the last near-millenium—leads to the kind of power accumulation that erodes or outright prohibits these freedoms.

“The freedom to move, the freedom to disobey and the freedom to create or transform social relationships.”

“Progress” is never a clear path; it’s a messy, tangled walk through an overgrown forest that often leads in circles. The benefits of whatever we call progress are only fully realized when they come hand in hand with an awareness of wealth’s downfalls.

The second response is to pay serious attention to building parallel systems that not only show the viability of, for example, commons management of land and life, water and work, but have the resilience to keep going even when shit does hit the fan—which systems run by and for wealth and power are generally too fragile to withstand.

There are plenty of examples of these systems being built right now, probably all around each of us, that we might be unaware of because they aren’t the stories that grab national and international headlines. But the podcasts Frontiers of Commoning and Building Local Power, for example, both focus on efforts around cooperative farms, community broadband, watershed citizenship and bioregional activism, Rights of Nature, tenants’ rights, composting and food security, and more.

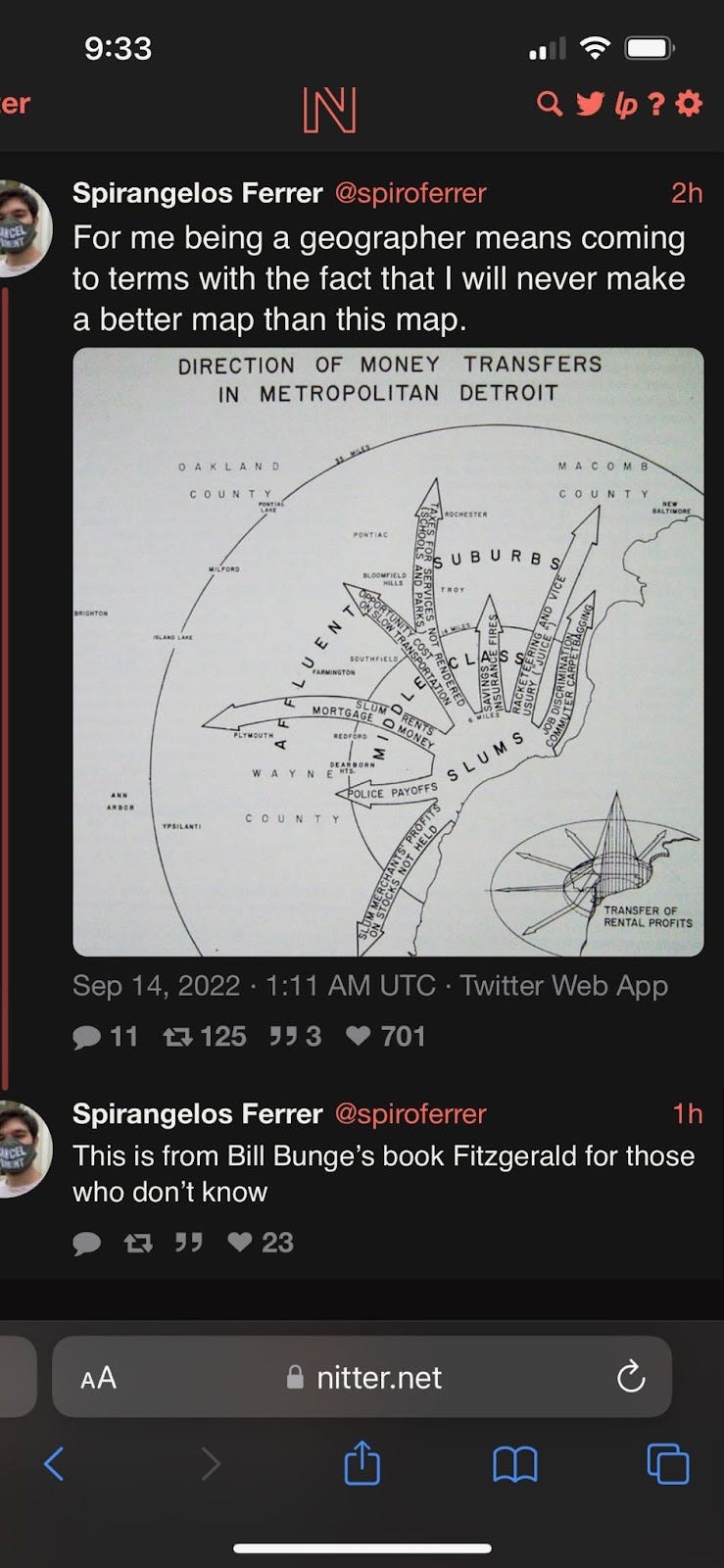

The more a society is designed to crush you, though, the harder it can be to make these efforts successful. In my book A Walking Life, I wrote about the St. Paul, Minnesota, area of Rondo, a majority Black community of thriving businesses and neighborhoods, which was largely destroyed, losing over 700 homes and 300 businesses and the community split in half, to build a now 8-lane freeway during the U.S.’s highway-building craze in the middle decades of the 1900s. It’s a far too typical story. Most of the U.S.’s major highways, where they run through cities, were built by destroying mostly majority-Black and poor communities, along with any equity they’d built in those businesses and homes, and largely to serve more affluent suburbs.

Wealth gets its resources, including power, by extracting from everyone else in any way legally possible and many illegal.

You can’t separate injustices from one another without power weaponizing that separation to eradicate resistance—or attempting to.

The right to vote, for example, has long been entwined with wealth, specifically wealth of land. In 1819, a peaceful rally of nearly 60,000 unarmed working class people in Manchester, England, was organized to advocate for the right to vote for those who did not own property (the U.S. Constitution, too, originally limited voting rights to property owners in addition to requiring that they be male, white, and over the age of 21). Land enclosures—theft of the commons—going back as early as the 13th century meant that very few people owned land, but laws they had no opportunity to participate in writing affected them anyway.

Government forces attacked the peaceful rally, resulting in 18 dead and over 650 injured in what is called the Peterloo massacre. Those who didn’t own property wouldn’t get the right to vote until the late 1800s.

Self-taught American economist Henry George spent most of his 1879 book Progress & Poverty writing about the ways that land ownership leads to wealth inequality and accumulation of political power by a few, and resistance to the same:

“Absolute political equality does not in itself prevent the tendency to inequality involved in the private ownership of land, and it is further evident that political equality, coexisting with an increasing tendency to the unequal distribution of wealth, must ultimately beget either the despotism of organized tyranny or the worst despotism of anarchy.”

If normal, everyday people understood the reality that all wealth comes from land, from nature, as well as from the labor of others, human and non-human alike, they wouldn’t vote for a system that gives yet more wealth and power to those who already have it, that hands power to those who control land and are therefore able to accumulate wealth.

But as should be painfully obvious by a simple glance at the daily news, mass understanding of that reality requires more than education; it requires imagination and insight. It requires that those who do the storytelling—journalists, reporters, novelists, and poets—share experience with the bulk of humanity, at least enough to access some empathy, to be able to put themselves in other people’s shoes. To understand that what they’re being told by those in power might simply be a story benefiting and protecting the same—power, and wealth.

It takes a lot of imagination and intention to see where our own privileges have blinkered our vision. If I had come from a family with even middle-class income, if my parents or grandparents had money and I weren’t working more than one job at a time just to support myself and be able to finish college, I could have taken that internship with a prestigious literary journal. I could have started climbing some kind of literary ladder, become an editor at an equally prestigious publisher maybe. And I maybe would have assumed that it was only my hard work and talent that got me there, not seeing the ways the trail was cleared and the path smoothed before I ever stepped on it.

We all need self-awareness to be able to see how power is actually structured, how it is shaped around the interests of wealth and property. That there is no “trickle-down,” that enormous accumulation of wealth is detrimental, actually, to life and freedom at every level you can think of, including the individual lives shaped and softened by wealth itself. All of this requires an understanding of propaganda and Story and how deep attachment to identity—both individual and shared—runs through every human being.

It requires a shift in consciousness, you might say, as well as changes in tax codes and societal priorities.

Or there’s a third option, which is to wait for the incompetence and nepotism inherent in oligarchy to eat their own power structures from the inside out.

The philosopher Aristotle, who made an extensive study of the rise and fall of city-states, rulers, and power structures in his book Politics, written over 2300 years ago, warned that oligarchies are inherently unstable. They can’t meet the needs of the regular population, they can’t abide competition in business or culture, and they can’t be bothered to follow the laws they write, even those that benefit themselves.

In a video summation of oligarchies, how to fight them, and Aristotle’s Politics, the narrators of the YouTube channel Legendary Lore1 said that,

“Aristotle observed that while a state can handle many types of protest, the real danger comes when people stop believing the state serves its proper end: the good life and virtue of its citizens,” resulting in an erosion of legitimacy.

“Aristotle warned against the wealthy treating common things as their own, like when public spaces become effectively private, when shared infrastructure serves only elite interests, when common goods like water and, in our times airwaves and digital networks, become de facto personal property of the economic political class.”

Oligarchies tend toward nepotism and its ruling members live openly in opposition to the laws imposed on the rest of the population. Their networks become brittle, and the systems often succumb to infighting among oligarchs themselves.

“Many oligarchies,” Aristotle wrote in Politics, “have been destroyed by some members of the ruling class taking offense at their excessive despotism; for example, the oligarchy at Cnidus and at Chios.”

We can wait it out, knowing that not only does everyone else suffer in the process—and it’s a long process; some form of oligarchy has been in charge of Russia going on decades now, culminating in the theft of Crimea in 2014 and the invasion of Ukraine in 2022—but the reality of wealth will likely, in the long run, still protect many of those who caused the damage. And then the cycle can start all over again.

One of the biggest things I learned while writing my book about walking was that connection, care, and community are just as core to our evolution, just as ancient if not more so, as any of our worst tendencies. If humans were all despotic, greedy, and evil, our species wouldn’t still be around. There are hundreds of thousands of years of archaeological evidence showing us capable of greed but even more of cooperation, and we have the opportunity, in every generation, to choose which of those tendencies we reward, strengthen, and build societies upon. Likewise, that reality inevitably gives something to build hope upon.

“If mutual aid,” wrote Wengrow and Graeber in The Dawn of Everything,

“social co-operation, civic activism, hospitality or simply caring for others are the kinds of things that really go to make civilizations, then this true history of civilization is only just starting to be written.”

My own energies tend toward helping to build, support, and research and write about those parallel systems, usually hyperlocal, that go under the radar but that provide examples for lifeways that make societies life-supportive, locally adaptable, self-aware, and achievable. St. Paul’s Rondo, for example, has never stopped working to repair the damage done by the building of a freeway, and restore its community.

It’s not sexy or loud or charismatic, and it’s not going to topple globally powerful and corrupt international criminals hell-bent on making everyone else suffer. It certainly won’t make me or anyone else whose attention is directed that way famous or rich, nor will it save us all from authoritarians and murderous dictators next week or feed all the children tomorrow.

But it’s still work that’s needed, and in the long run, with enough people, its own power might surprise us.

The law locks up the man or woman

Who steals the goose from off the common

But leaves the greater villain loose

Who steals the common from off the goose

The law demands that we atone

When we take things we do not own

But leaves the lords and ladies fine

Who take things that are yours and mine.

—from 17th-century protests against English enclosures