Swan Lake, Montana, nearing sunset, through the smoky haze of a nearby prescribed burn.

In 2016, a month or two before that year’s U.S. presidential election, I was at a two-week interdisciplinary artist’s residency at the Banff Centre for Arts & Creativity in Banff, Canada. We had dancers, writers, visual artists, actors, composers, and musicians in our group, with writer Pico Iyer, musician Richard Reed Perry (of Arcade Fire), and choreographer Christopher House leading workshops.

The residency was formed around the theme of the Art of Stillness, taken after Iyer’s recently-published book The Art of Stillness, with a series of weekend workshops on stillness open to the public—like forest bathing, a Japanese tea ceremony, concerts, and a series of talks on Deep Listening that might have contained one of the most powerful experiences I’ve ever had.

With Iyer, we discussed writing of stillness, and stillness practices. Perry had us listen to our own heartbeats and breathing through stethoscopes, and composed music based on the rhythms we tapped out.

It was a beautiful two weeks, easily the best residency I’ve ever been to. I attended another three-week writing residency in Banff two years later, and decided that interdisciplinary ones are far more inspiring. There’s a cross-seeding of creativity, of playing in unfamiliar forms like (for me) dance and composition. All of us who attended the Art of Stillness have stayed in touch over the years (one of our group, writer and physicist Wendy Brandts, passed away in 2022) and followed one another’s work. Stories shared in that group made their way into A Walking Life, and the book itself was largely shaped by the lessons I got to soak in for those two weeks.

Every morning, Christopher House offered a movement session before we each went off alone to studios to do our day’s work. I can’t remember what kind of music he played or if he gave us much direction in the dancing, but there was one line he repeated day after day, in those movement sessions and in his own presentations and workshops: “We are exploring the deep ethics of optimism.”

I wrote about that line off and on at the time, and remember posting something on Instagram the day of the presidential election with simply that line and a photo of the bitterly cold, snowy morning, Sun’s rise refracting off ice-glazed caragana branches.

That was in 2016.

I wrote about the deep ethics of optimism leading up to that election because I couldn’t figure out what it meant. I’ve thought about it frequently ever since and still don’t understand what it means. The deep ethics of optimism. What does it mean, what does it mean?

I have a feeling it’s the kind of idea I might have an epiphany about just moments before I die. I hope that moment is a long way off, but I look forward to it.

And it’s a thought I find myself wanting to share now and again. Maybe I’m hoping one of you will have an answer. Maybe I hope that for one of you it will be an answer—in the way that I say walking is, not something that gives an answer, but whose action, whose exploration, is an answer in itself.

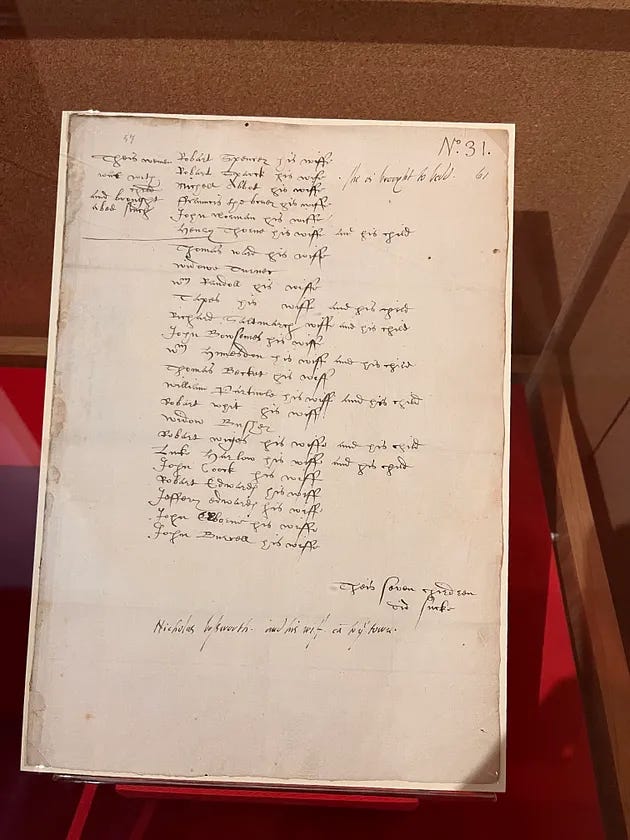

We are exploring the deep ethics of optimism. Maybe it’s what brought me to writing more seriously about the commons—I’d published my first essay about the commons and land ownership in Aeon earlier that year. Freya Rohn, who writes the Ariadne Archive, recently sent me photos of “a list of women who were named as defying enclosure laws and were imprisoned and executed” in rebellions against enclosure—theft of commonly shared land in England—in 1589.

The optimism of the commons does not require building something new, but it does require an understanding of what has gone before. It needs us to see not only what has been lost, but that things haven’t always been this way. It’s why it was so important to me to write about centuries of violent rebellions against land enclosure in High Country News recently. The harsh restrictiveness of private property in land is very recent—while the same of ownership of people, especially women, and of food and seeds, is very old.

It is deeply ethical to ground yourself in the knowledge that humans have always, everywhere, shaped their worlds—our worlds—differently, have shaped them to treat animals with respect, revere trees, nurture kinship with rivers and springs, and at the same time care for people’s physical, emotional, and spiritual needs. To have, as my friend Sherri Spelic has written about with regards to education, Care at the Core, the kind of ethos that shaped economist Kate Raworth’s Doughnut Economics model, meeting human needs without straining ecological limits.

Maybe optimism is misunderstood. Maybe this is about the deep ethics of knowing, not just believing, that there are better ways to live. That it is possible because it has happened, over and over.

Maybe the deep ethics of optimism is more about what we think of human nature. It can be, and obviously is, dire, cruel, selfish, abusive. But it is also reflective of what a society rewards, what culture cultivates. Humans evolved in community, in interdependence. We wouldn’t be the species we are if we hadn’t cared for one another for hundreds of thousands of years. The paleoanthropological records are clear on this. Hominins evolved within the necessity and ethos of care.

Which means we can, with intentional effort, reward and cultivate behavior that brings care back to the core of human life. Given where we are, that’s not easy. Given where we are, it might be hopeless.

But given where we are, I can’t accept giving up on humans’ capacity to do better. People have burned down their worlds, and others’, countless times throughout history. In such times, those who suffer most tend to be those who have always suffered most.

A friend recently sent me some photos of her visit to Kara E-Walker’s exhibit at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. I misread text on the wall that read “A Respite for the Weary Time-Traveler” as “A Respite for the Weary Time-Tender.” It felt a perfect word-shape to hold the increasing everyday stresses of lives even without considering war, genocide, climate change, and the power of billionaires.

A respite from tending to time, because we are weary.

We are weary. We need respite.

We are exploring the deep ethics of optimism. Maybe all it is is being alive, and loving this world with our whole hearts, despite everything that seeks to break us.

First snows! Looking out toward the peaks of Glacier National Park recently in Montana’s North Fork Valley. ☃️❄️🏔️