Some years ago when I still lived I upstate New York, I began working at a sawmill. I had two very small children at the time, and had never intended nor desired to be a full-time stay-at-home mom, not to mention be one and working at the same time (due to the full-time stay-at-home mom reality, most of my work happened in the middle of the night, a capacity I no longer have). But I was doing exactly that, and rapidly dying inside because staying at home with children all day is not, to put it mildly, my calling in life.

One of my kids went to part-time preschool twice a week at a nature museum, which also offered adult classes like beekeeping and wild foraging, both of which I took—out of curiosity but also to stay sane—along with rustic woodworking, an activity I’d never imagined myself doing. I am the kind of person who can’t be trusted with a table saw or even, frankly, a spirit level. The rustic woodworking artist who taught the class introduced me to New York Heartwoods, a micro-mill run by a woman (coincidentally, also from Montana) who’d bought a Wood-Mizer LT40 and specialized in milling wood from downed and diseased trees on public and private land.

Working at the sawmill a couple days a week—interning, really, since I was there to learn and wasn’t being paid—helped keep me from going completely numb, from depression and dissociation from life, and it got me into research on embodied learning, but I was also intrigued by the mill’s mission: the owner only worked with fallen or scavenged trees. The point of the mill was to introduce circularity within the wood milling system, which fit right in with efforts I’d been making toward supporting local food systems and fending off long-term despair over single-use plastics.

We worked with a lot of city Ash trees felled by emerald ash borer, and Cedar that had been cleared from farm fields. I spent one entire day planing Cedar planks for someone who’d rescued them, already milled, from her family’s farm and was making an art installation out of them.

Another time we spent most of a cold, snowy day dragging out enormous old beams from a fallen barn, taking them back to the mill to be sawn into boards that would be lightly sanded and used to make shelves.

The mill’s shady, forested yard was full of beauties, every one of them cared for, whether already milled and kiln-dried or not. I don’t ever plan on moving away from Montana, whose forests are full of soft-wooded Pine and Fir, Aspen and Spruce, but do sometimes miss working with hardwood.

One day, we were milling reclaimed beams from an old barn for a client. Old barn beams are a pain because they’re often full of nails—long, heavy, rusted nails that are hard to spot. We ruined a few blades as hidden nails made it through and wrecked the metal, and finally gave up. That barn beam went back to its owner, or maybe to a scrap pile, joining the piles of beautiful wood resting around the property, testimony to one woman’s commitment to making sure their lives continued.

It only occurred to me later to wonder why we hadn’t taken the time to look for and remove the nails ahead of time, why we sacrificed several saw blades and in the end the beam itself rather than take the time to remove as many nails as we could find and make the wood workable again. It obviously would have been a waste of time, but then again, the entire endeavor could be classified a waste of time, if all we use for measurement are the standards of capital and efficiency.

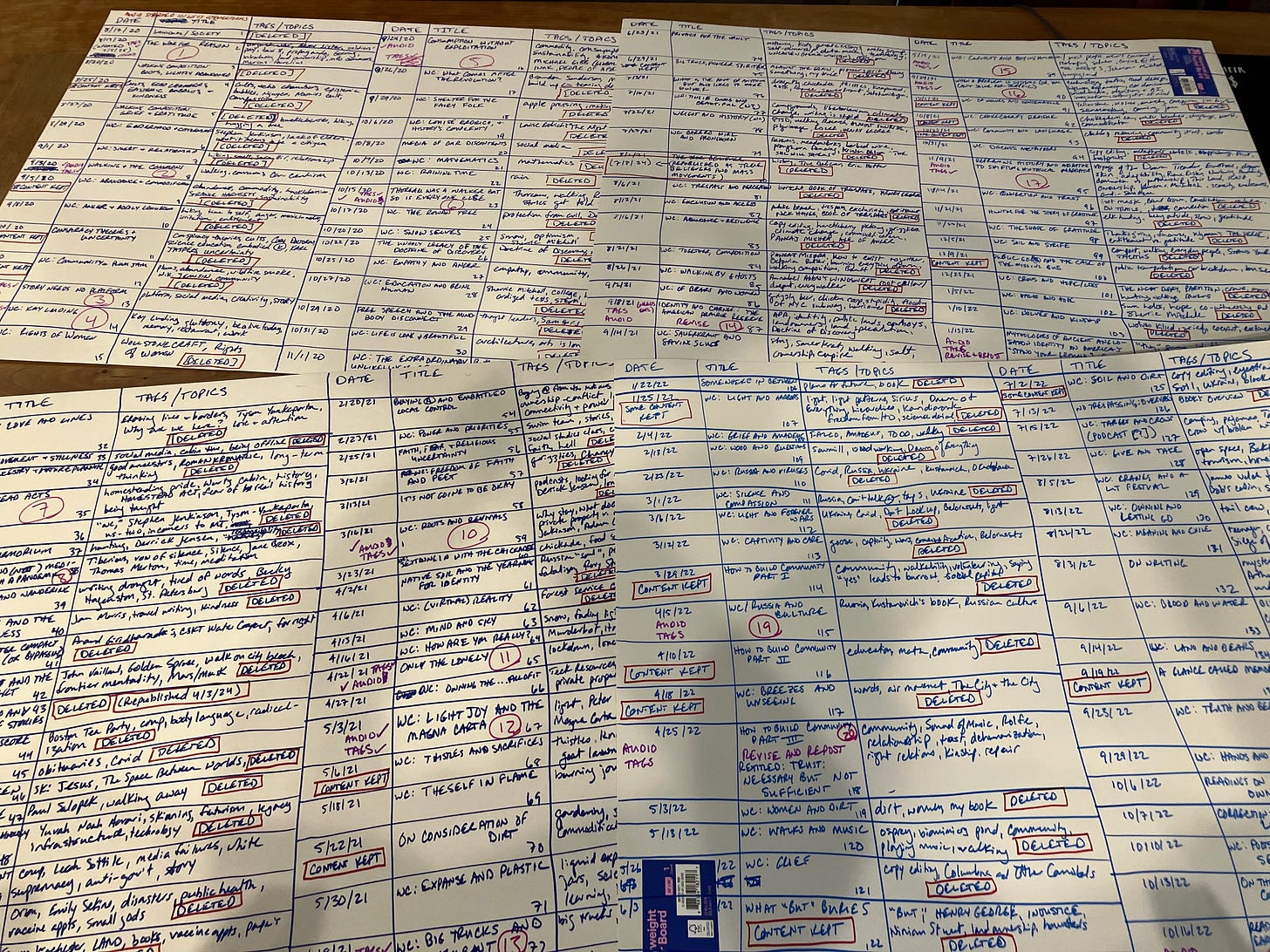

A couple months ago I succumbed to the urge to crawl through all the essays and posts in this newsletter, starting from the very first essay in late summer 2020, about Marcus Aurelius and my own cognitive disconnects around the U.S. invasion of Iraq, when my older sister was still in the military.

I ended up deleting almost 200 out of nearly 300 essays and posts. Some were from before Substack launched its Twitter-like Notes platform, and were brief photo + quote + sentence or two “walking compositions,” a practice I’d migrated over from my deleted Instagram. Many posts I thought were pointless, and others need more revision work. The ones I kept, I’m slowly revising and recording audio for, since I only started doing audio versions in late 2023 (I’ve made my way through nearly 20, starting from the beginning).

Many of the posts and essays I deleted, I saved in offline Word documents, collecting them by theme. By far, the largest of these collections is one I’ve labeled “Abundance and Commodification,” with over 40 pages of text. Some of what I’ve rewritten here about my time working at a sawmill are lines scavenged from that document.

Out of all the writing I do on the commons, the complementary topics of abundance and commodification—of food and seeds in particular, but of everything in general, including labor, creativity, and ideas—overwhelms the amount I have written about land ownership, which surprised me because I feel like I never shut up about land ownership, and repeat myself to a tiresome degree.

Something about rereading all of those words and stories, and collecting together the ones that I felt needed more editing, or perhaps shaping into a larger, more cohesive project, reminded me of my faith in storytelling, how deeply I believe in its power, and in the world’s need for it. For more stories, stories with heart and truth, as many as possible from as many different perspectives as possible, especially from voices, people, and places who’ve been heard the least. Every iteration, not for the purpose of telling anyone else how to feel or what to think, but sharing the unique experience of what it is to live one’s own individual life. The joy, the pain, the traumas, the grief, the love, the visions and losses and hope.

I don’t think we can ever have enough ways to help ourselves feel what it’s like to live in someone else’s experience.

Yet it often feels like the world is awash in stories. Good stories, important stories. Stories we need to hear and stories we need to tell. Fantastic fiction that opens up possibilities for imagining different ways of living; investigative reporting that unfolds the truth of the world. I have been floored by the work of brilliant documentary filmmakers, by novelists who are bona fide geniuses, many of them personal friends.

And what changes?

It is very easy for the path opened up by that question to lead to despair. I’ve been there myself more than once—I’m there myself more than once on any given day, and I don’t think it’s solely a genetic half-Russian Jewish fatalism. It’s looking at the world, and humans, as clear-eyed as possible. It’s seeing people I believed in and trusted coopt genuine need and good causes for their own benefit; it’s seeing the hard work of millions crash against the walls of capital and power.

But down that path is also possibility. My father used to say, and still does, that the biggest problem in the world is lack of imagination. He meant a capacity to place ourselves in other people’s lives and experiences, a capacity for empathy. It’s both true and bigger than that.

Every story shared is a chip in the systems and structures that seem unbreakable and insurmountable. Most of the time we don’t see what’s changed until long after the fact. Real life isn’t a Hollywood apocalypse movie with sudden shocks to the system and people screaming for the walls. We’ll never know what cracks it all open. But those stories, that work, looking at life slant and seeing what can change, that’s how the light gets in.

After taking my first rustic woodworking class, I couldn’t get enough of working with the diversity of hardwoods that grow and fall in the U.S.’s northeast. I learned about the different high-end uses of varieties of Maple, and how bad Black Locust smells—there is no other way to say it but that Black Locust smells like ass—but also how useful it is. Black Locust is so hard that it can be used in decking. It’s like cement board.

I learned how bacteria and fungi cause spalting and how beautiful its black lines are lacing through decaying stumps or sawn boards. In midwinter, the mill’s owner sent me on a day-long chainsaw safety course, where, after several hours of learning to care for chainsaws and safety equipment and looking at photos of people who’d had horrifying accidents, I stood in knee-deep snow and cut down a Pin Oak. I decided I never wanted to use a chainsaw again because I am clumsy and it was terrifying.

The entire project of New York Heartwoods was at core anti-capital. It was inefficient, time-consuming, space-consuming. Slow. Laborious.

It was an enormous amount of work simply to find markets for the wood products, much less retrieve the trees and logs and mill and kiln-dry and shape and sand it all. That entire day one employee and I spent planing someone’s recovered stack of Cedar planks? The client probably could have bought something similar from IKEA for far less money than that day’s labor cost. Even though I was working at that sawmill for free, nobody else was.

But that’s the point. The work was slow and laborious. And smelled heavenly. I could eat my winter-cold sandwich on a stump of spalted Sugar Maple and smell the melt-snow damp of coming spring. I could peek into the kiln and its stacks of Ash boards. I could do work, and feel alive while doing it.

What does efficiency in our lives get us? The question sits like an invisible monster in the center of capitalism: if “the economy” isn’t there to serve human and ecological well-being, what is the point?

If working with wood by hand gave me and others pleasure and satisfaction, and gave clients connection to their ecosystem and its cycles, why not engage in that kind of work? And why are we prevented from doing that work simply because it doesn’t provide enough income to feed our families?

It’s the reason I recommend reading Wengrow and Graeber’s book The Dawn of Everything as a balm for despair. Or at least listening to interviews about it, or reading summaries. Whatever works. It’s an enormous book and what’s important is the message behind it: there have been countless ways of forming human societies over the past several thousand years. Just because our current industrialized culture feels like some kind of inevitable endpoint doesn’t mean it’s true. Those endlessly varied histories remind us what might be at the core of true freedom.

It also gives an opening into that question, “What changes?” Well, a lot can change. We never know how, not completely. Working toward change for the better doesn’t guarantee success, nor does it guarantee lack of pushback, but without stories we don’t even know how to imagine something different.

I heard someone recently—one of the tarot readers I follow on YouTube—talk about leaning into fear with curiosity. Despair, too, I suppose. That’s where we can find self-empowerment, and perhaps an entirely different way of perceiving both problems and possibilities.

Like in K-Pop Demon Hunters: perhaps a failure to seal the Golden Honmoon isn’t a failure at all. Maybe it’s a way to discover something more powerful and more honest, with a capacity to connect us all.