In late 2016, a . . . situation, let’s call it, battered my town. A neo-Nazi site had picked up a disagreement over a local building’s ownership, and the result was months of online and telephoned threats to many people in town, one family in particular, and a threatened armed march that we all prepared for but that never materialized. Possibly because it was never going to but also possibly because that was a bitter winter; if I remember, the day of the proposed march was -17°F (-27°C).

Reporters covered the situation so thoroughly that for a long time you couldn’t google my town without white supremacists being the top story.

The targets of the attacks were pretty much all Jewish, or even seemingly Jewish. At least one business in town was attacked until the neo-Nazi site’s owner found out the owners weren’t Jewish. The “troll storm” (a term I dislike; it makes it sound like a game and attacks like that are anything but a game) was vicious, and left scars that will probably never disappear.

As the attacks started, a friend asked me for help figuring out if there was a way to protect the identity of one of the victims. I’m not a cybersecurity person or even an investigative journalist, but I tried. I spent a night crawling through 4chan and 8chan threads (I do not recommend this for anybody ever) but it was too late to stop personal phone numbers and names from getting out.

That same week, by sheer coincidence, an op-ed I’d written was published in the Los Angeles Times, tangentially related to the already-ongoing situation. I’d written it because one person had already made my hometown synonymous with white supremacy and, since I’m a writer and had an editorial contact at the paper, writing was all I could think of to help.

That op-ed turned me into a target, too. What I experienced was absolutely nothing like what other people went through. I describe it as receiving barely a splash from a tsunami that hit others with full force. I wrote about that in more detail a couple of years ago, including screenshots of the Twitter posts directed at me, in an essay about the digital commons and the ignorance in thinking that what happens online has no true real-life consequences:

I still had a Twitter account then and kept screenshots of some of what was sent my way, which wasn’t notable for its level of hate, but for the fact that the person writing the posts knew my nickname (which I’d almost never shared online before), my phone number (ditto), and my family’s routines. Which meant they either knew me or knew someone who did. I’ll never forget walking to the elementary school playground day after day, wondering who?

Who had given my phone number and my family’s personal details to white supremacists? It was someone who knew me.

Even before someone posted my phone number on Twitter, before I had much of a personal reason for fear, I was scared. The relentlessness of this “troll storm,” the sheer hate and dehumanization behind it, still makes my skin crawl seven years later. I was scared for my friends and acquaintances, my community. I was scared for what it said about what kinds of forces were being empowered worldwide.

I’m not the only person who coped by drinking a lot, by spending time only with people I trusted absolutely.

I stopped being able to sleep much. I mostly consumed chicken wings and booze. I had been walking or biking my kids to school day in and day out for two years, morning and afternoon, ever since my son started first grade, and was suddenly terrified to be physically outdoors, with them, visible. Being a target myself was bad enough; I didn’t want anybody to know who my kids were.

The day of the march came. None of the threatened participants showed. The town had shut down in preparation anyway, so as to withdraw as much attention from the attendees as possible, and a group hosted a matzo ball soup gathering in an emptied downtown. I wasn’t there. I can’t remember what I did that day—watched The Lego Movie with my kids, maybe, for the tenth time (my choice, not theirs; I enjoy that movie). I think we had a fire going in the wood stove all day. Hunkered down in warmth and seeming safety, even if safety is always a mirage, a veneer. Temporary.

The troll storm faded away but the fears and damage didn’t. Everyone, I imagine, learned something different from that time. Everyone, I imagine, learns something different from all such times.

I’m under no illusions that the threat has faded. Anti-Semitism is perhaps, except for misogyny, the oldest and most universal prejudice on the planet, stretching back through massacres, wholesale expulsions from entire countries, theft of children, and vast, structured oppressions for nearly 2000 years. There’s a reason Daniel Goldhagen titled his book about anti-Semitism The Devil That Never Dies. My grandparents in Russia lived that history. Anton Treuer, known most for his work on Ojibwe language and culture revitalization and his YouTube channel featuring an Ojibwe Word of the Day, but whose father was Austrian Jewish, has said that the scope and scale of this history should make Jews, of all people, most acutely aware of the injustice and horror of oppression and genocide.

If it’s not anti-Semitism, there are plenty of other targets for hate, fear, and power-hungry greed, as likely everyone reading this already knows.

Everyone, I said, learns something different from these times, is damaged differently and finds different ways to cope. I’m not here to tell you how you should feel when times are frightening or worrying, or that your fears or worries are greater or lesser than another’s. I can only share my own story. Really, that’s all any of us can do.

The troll storm and threats happened just a couple of months after I signed the book contract for A Walking Life. That time had a lot to do with the parts of the book that focus on social capital, social and interpersonal trust—including their fragility and how authoritarians can weaponize them—and the ways in which authoritarian regimes use loneliness and a sense of isolation to fracture the power of resistance, a dynamic that Hannah Arendt covered decades ago in The Origins of Totalitarianism.

In times like these—in all times—trust is essential. But it is easily broken and easily coopted, especially with the reach of the online world we now live with. One of the things that came through during those months, for me at least and this is part of why I wrote about community and interpersonal trust so much in my book, is that the voices I’d followed online, or in national or international news, were most often almost powerless to help my community, and in some cases caused more damage than good, even when well-intentioned. And not all of them were well-intentioned.

Lauren Hough recently wrote a brilliant piece mentioning the creation of “an entire industry of resistance grifters” after the 2016 election, and Dr. Len Necefer, founder of NativesOutdoors, also recently wrote something addressing that idea more directly:

It’s worth pausing to ask yourself: Why do you follow the influencers you do? This question isn’t about what they say or how they frame their ideas but about the underlying mechanics of why they have your attention in the first place.

I added the emphasis in Necefer’s because it strikes me as an essential question each of us needs to ask ourselves, especially when we’re living with uncertainty and looking for direction.

Both those pieces are necessary reminders of the power of attention, how it can be manipulated, and how it can be used to others’ advantage.

They’re also reminders that not everything or everyone you already agree with, or who seems to care about the same things you do, is acting with anyone’s interest but their own in mind.

In times like these, it’s tempting, it’s human and natural, to look to others for guidance. But as helpful as that can be, there are risks inherent in it, too. More than once I’ve been an avid follower of a writer who seemed to articulate my own thinking to me, who seemed to care about the things I cared about, only to watch that person grow in success and lose their mask, become more truly themselves—prejudiced in various ways, desirous of power over others, unwilling to promote a cause or event unless they were its main star. I don’t know whether enormous ego is born from mass attention and some level of success, or if ego is drawn to the same and feeds off of it, but I’ve watched it happen to enough people whose work I used to like and ideas I used to look up to—during that “troll storm” and again as Covid spread over the world—that I began to question my own judgment. I see it happening again now.

Voices and people we trust can be corrupted by the lure of power and influence, by the attention of masses, and they can forget, if they ever knew, why their work, words, and influence matter. It can happen to anyone. Be wary, is what I’d say, of anyone telling you they’re on a divine mission, especially if they’re asking you for money.

We are all unique, brilliant beings with our own purposes, full of hope and doubt and hidden shadows most of us don’t like to acknowledge. If any one human has a divine mission, we all do. But maybe none of us do. Maybe being alive, being able to touch and smell and love the world, is enough. And no matter how charismatic, how compelling, how persuasive, nobody can be you for you any more than anybody can take you from you. Finding a way to believe and understand that with one’s entire being might be an essential survival skill—collectively as well as individually.

There are some books that helped me in the last eight years, books that I turned to to regain perspective and that I might pick up again: We Are the Middle of Forever: Indigenous Voices from Turtle Island on the Changing Earth, edited by Dahr Jamail and Stan Rushworth; The Art of Happiness in a Troubled World, by the Dalai Lama and Howard Cutler; Walking the Ojibwe Path, by Richard Wagamese, Pankaj Mishra’s Age of Anger, bell hooks’s Belonging, and The Unwomanly Face of War, by Svetlana Alexeivitch. They’re books that at least try to eschew generalizations, that insist on the specific, the individual, narratives that question and explore rather than demand or insist. They remind me, in fact, of why I’m such a big fan of good science fiction writers like N.K. Jemisin, Arkady Martine, and Martha Wells. Stories that remind readers that we often know far too little of any other person’s story and motivations, that caution us against assuming we know anything of their lived experience, of who they are.

But I can still only be me, with my own story, so I go back to my ancestors, especially my grandparents, all of whom I’ve been spending more thought-time with recently, looking for guidance and resilience that I know will never truly be found outside of myself.

My ancestors didn’t gift me with much tendency toward hope, and, despite my Russian grandfather being sent to fight on the German front in World War II with one rifle and no bullets shared between three people, not much of a fight instinct. But they did leave me with a kind of determination and—I feel extremely lucky in this—a strange capacity for joy and humor even in the darkest times. One of my favorite quotes, “Blessed are we who can laugh at ourselves, for we shall never cease to be amused,” by an anonymous author, is a personal mantra.

On the nights I allow myself to crumble into tears, fear, and despair, I think of my Russian grandmother as a refugee from the four-year Siege of Leningrad, in the Ural Mountains, her hands bleeding from hoeing potatoes to keep her children and mother-in-law alive, and I look at the pictures I have of her, her soft smile and eyes kind after a lifetime of oppression, prejudice, and hardship. I think of my grandmother in Montana, the decades she spent in Great Falls working as the director of public assistance for three counties, her compassion and absolute dedication to public service, the lives she touched, and the quiet ways she lived out one of her favorite lines: “Those of us entrusted with positions of power must remember never to abuse it by failing to respect those who seek help.” I remember how unassuming and intensely private she was, how much she loved dogs, and the way she smiled, with her whole being, when amongst friends.

I don’t know what the next months or years will bring. But I know what my community has shown itself capable of withstanding and standing up for over the decades, and I know that chicken wings and booze will not erase my fears when they overcome me. Nothing will. (No judgment here—for someone else, chicken wings and booze might work just fine.) My fears and heartbreaks can only be faced with as much strength and compassion as I can muster in between the fallings apart. And with that fragile trust built within actual relationships with actual people. And maybe the occasional basket of tater tots and my newfound addiction to watching tarot readers on YouTube.

Gandalf’s words when Frodo said, in The Lord of the Rings, “I wish it need not have happened in my time” are never not apt: “So do I. And so do all who live to see such times. But that is not for them to decide. All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.”

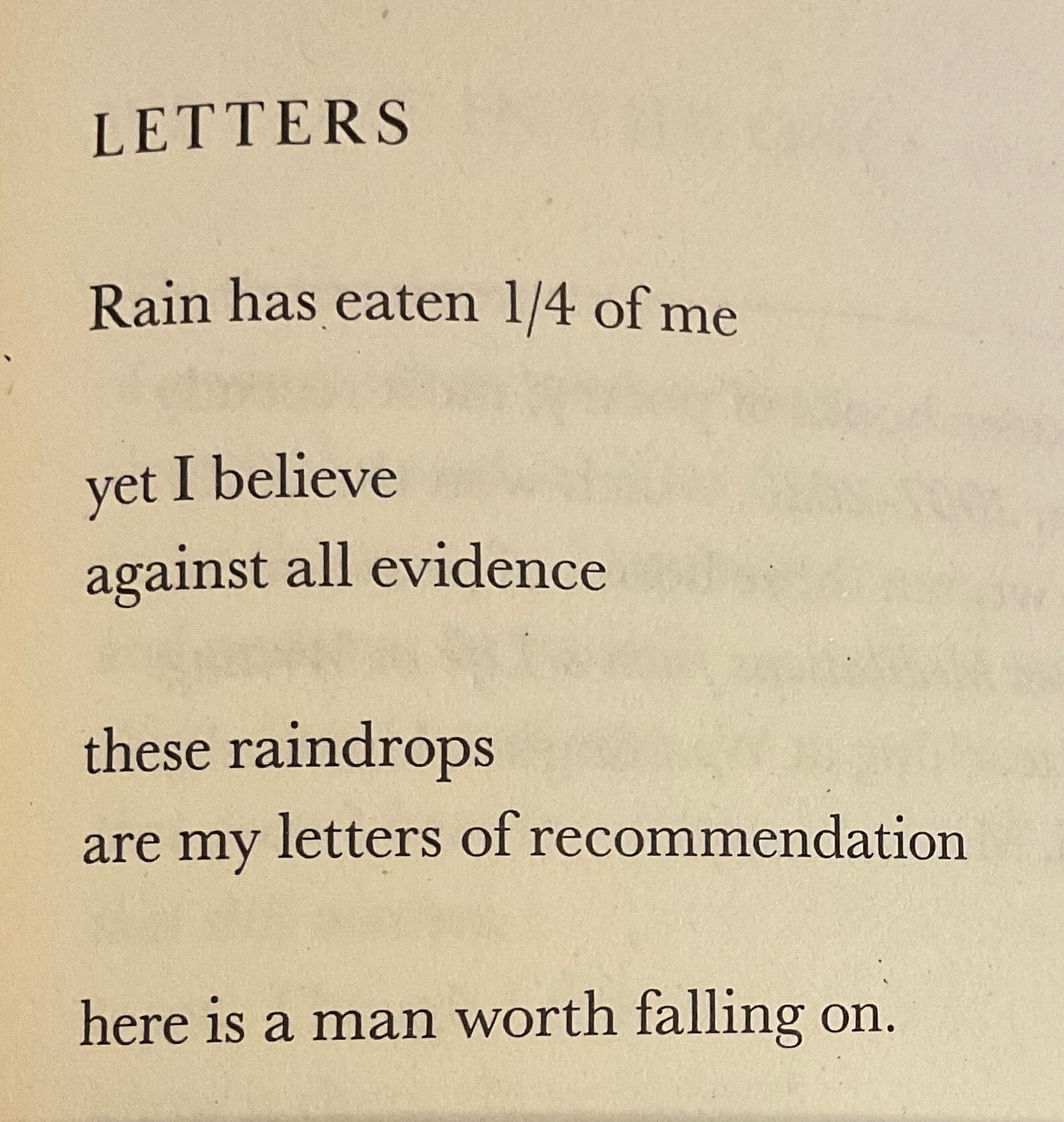

The Substack version of this essay has a recording at the end of my father reading his translation of Aleksandr Kushner’s poem “We Don’t Get to Choose.” I haven’t yet figured out how to include those audio recordings here–apologies!